A Month of Reading Exclusively Queer Literature – 50 Years After Stonewall

On the night from the 27th of June to 28th of June 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn at Christopher Street in New York City. The raid sparked resistance and a revolt against police violence over the following days. The exact sequence of events from these days and especially of the early morning hours at the 28th is difficult to retrace today. Even though, it is important to note that the riot involved prominently BPoC trans women and drag queens, sex workers, butch drag kings etc. Morgan M Page, writer and host of the trans history podcast One From the Vaults, writes in her article “It Doesn’t Matter Who Threw the First Brick at Stonewall“:

This uprising against police raids birthed the first Pride parade—the Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade in 1970—and has gone on to inspire LGBTQ communities across the world. “Stonewall” has become a metonym for queer struggle and resistance.

But even by the end of the 1980s, the events of those muggy nights on Christopher Street had already entered the realm of myth and speculation. Arguments over who started the riots have become an integral part of the Stonewall oral tradition, shifting significantly over time.

Page writes about some of the prominent figures around the Stonewall, their (contested) roles, but also their work in the years after that June 1969 which helped manifest Stonewall as a cornerstone in LGBTIQ history (especially US history, but not only). Page concludes:

What we think we know about Stonewall might be, at least in part, a myth. But here’s the thing: Humans need myths. Myths are how we organize our world and understand our place within it. Considering the global backlash against LGBTQ rights—from the threat of the reintroduction of the death penalty in Brunei, to constant attacks on trans rights in the British press, to the Trump administration’s near daily-assaults on existing protections—we need the myth of Stonewall more than ever to teach us its fundamental message. That it takes not one hand to throw a brick, but 10, 20, 100 hands working together across difference to ignite a movement.

In a special Harper’s Magazine asked eight writers – Alexander Chee, T Cooper, Garth Greenwell, T Kira Madden, Eileen Miles, Darryl Pinckney, Brontez Purnell, and Michelle Tea – what Stonewall means to them. Well worth a read, even now – or especially now? – that June and the 50th anniversary has passed. The introduction to the special called “Stonewall at Fifty” points also to its complex history and place in queer memory:

Not everyone is comfortable embracing a Mafia-owned bar that catered explicitly to gay men as the heart of a remarkably diverse political movement. For others, the unquestioned dominance of Stonewall-as-origin-story unfairly consigns a series of earlier uprisings to historical oblivion. Nonetheless, the riots survive as a powerful example of resistance in the face of repression […].

To commemorate the Stonewall riot I decided to read exclusively queer literature this pride month (one of the things grown from the events in 1969). I thought about reading books which are directly linked to Stonewall but even more to read a variety of books representing different stories, experiences, and voices. But the undertaking led to another quite fundamental question:

What is queer literature, anyway?

Texts which feature LGBTIQ protagonists? (All) Texts by LGBTIQ authors? Texts which harness a queer aesthetic? (And what makes for a queer aesthetic?) Texts which are written for an LGBTIQ audience? Only texts which combine all or at least some of these aspects? This is a complex question and none I plan to answer conclusively. Personally, when I speak about queer literature I think of fiction which focusses on LGBTIQ characters or non-fiction which dominantly focusses on LGBTIQ people and/ or topics and themes. Preferably these books are written by LGBTIQ authors (primarily because I want to support out LGBTIQ authors). But I am also aware that not everybody is ‘out’ (whatever that means) or that identities can easily shift. Sometimes, I find it borderline creepy to see how readers ‘investigate’ authors. In the end, I judge the text by what the text does, how it portrays LGBTIQ characters, which perspectives are centred, in how far does it play into heteronormative ideas nonetheless.

Putting together a reading list

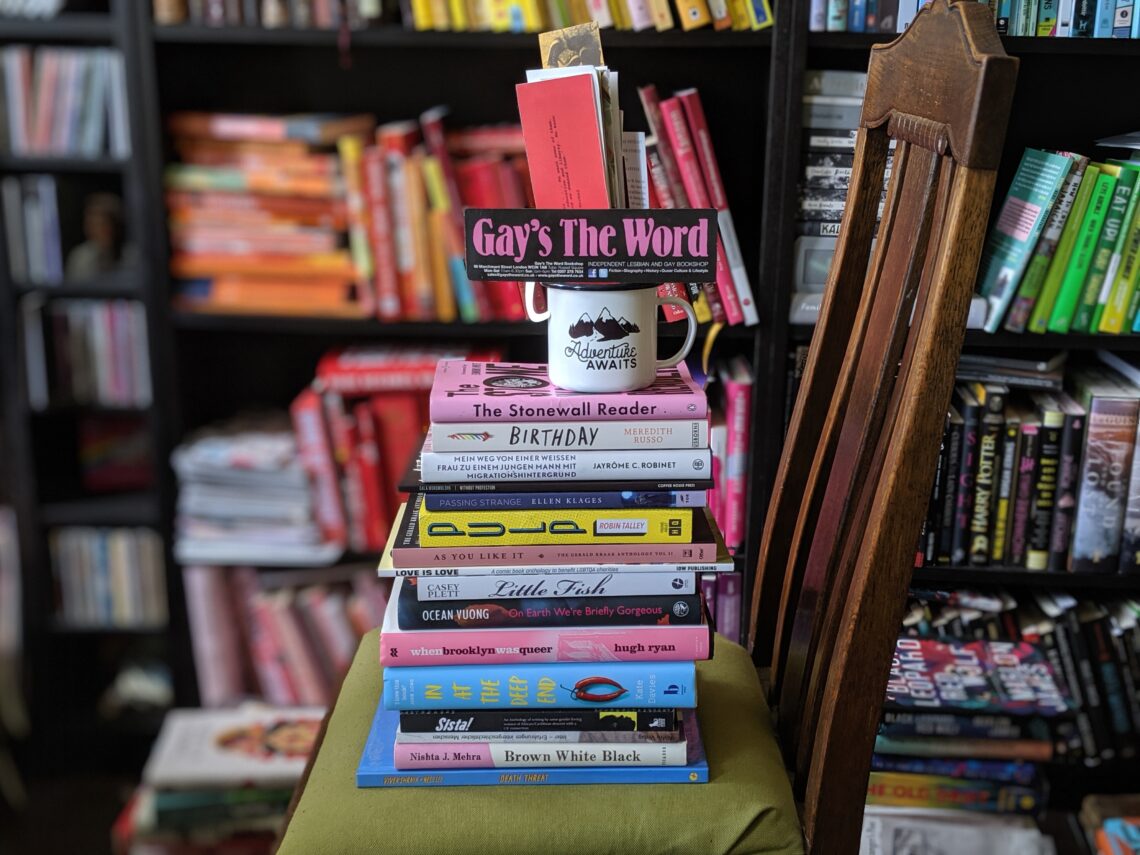

Deciding on what to read was not a particularly organized process. In May I put together a pile of books I already owned but had not yet read (mainly recent birthday presents and some books I had started reading at some point but left in the uncanny state of half-read but not abandoned yet). Then, of course, I also had my eyes on some new releases. I was a bit over-ambitious (which comes to the surprise of no one) and during the month my pile changed again and again. In the end, I managed to finish sixteen books and read substantial parts of six more.

June 2019

I tried to keep up with my reading diary – which was more successful on some days than others. I also interwove some snippets from reviews I wrote on Instagram/ Goodreads. Besides the books I read (and I almost exclusively write about those I have actually finished this month), I wrote about the Lambda Awards, two events I attended, and a podcast I recorded. It’s been a long June. And this is a long text.

1st/ 2nd of June – Enthusiastic first weekend

(Vivek Shraya Death Threat, Nishta J. Mehra Brown White Black: An American Family at the Intersection of Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Religion, Ellen Klages Passing Strange, Hugh Ryan When Brooklyn Was Queer)

Saturday morning even before breakfast I finished reading Vivek Shraya’s newest book: Death Threat. For this comic book, Shraya teamed up with the visual artist Ness Lee to create a book about her (Shraya) receiving threatening emails. The book is an illustration of what it means to be (a) woman/ PoC/ trans/ queer on the internet. It is not so much about just retelling a certain story but conveying the feelings you might have while being under attack. The colours are bold, often primary colours just slightly subdued, adding to the book’s urgency. Maybe it looks strange to start pride month with a book called Death Threat but it is more than befitting because it touches upon important realities.

I then went on to read Nishta J. Mehra’s essay collection/ memoir Brown White Black: An American Family at the Intersection of Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Religion. Mehra writes deftly about her experience as a queer woman (whose parents had migrated from India to the US) married to an older white woman and having adopted a Black boy who is gender-nonconforming. She examines the ways parenthood and family are constructed, looks into the anti-Black bias in the community she grew up in, lays bare her fears and wishes around parenting. There is so much in the book and I feel a lot of people could benefit from reading it.

The last book I finished this weekend was Ellen Klages’ Passing Strange. I was looking for a light, entertaining book and this one delivered: Klages wrote a wonderful romp about a group of queer women in 1940s San Francisco. There is art, science, and magic. It is a page-turner and I stayed up late to finish reading it and I did not see the last turns coming. The novella has a lot of elements I just love: Almost all significant characters are women and the book focusses on their different relationships, there is a sense of community and friendship, it dives into subcultures.

Besides these three books, I also started reading When Brooklyn Was Queer by Hugh Ryan. The book traces Brooklyn’s queer history from the 1850s to the 1960s. So far, I appreciated the careful way Ryan writes about shifting ideas around sexuality, gender, and identities.

3rd of June – Focussing on Inter Perspectives

(Elisa Barth et.al. (eds.) Inter: Erfahrungen intergeschlechtlicher Menschen in der Welt der zwei Geschlechter)

I bought this German-language anthology (the title roughly translates to “Inter: Experiences of inter people in the world of two genders”) some time ago and finally got around reading it. The aim of the anthology is to bring together inter writers, activists, and artists and portray their experiences – something which is rarely done. The introduction makes clear that this book is not meant to be representative but to shed a light on a variety of experiences. The anthology includes work by people from countries such as Serbia, Taiwan, South Africa, Costa Rica, and more. There are interviews, personal essays, photos, visual art. The pieces speak about the ways inter people are often violated, the shame and imposed silence, but also community building, activism, finding love, friendship, and paths to self-determination. The texts dive into the complex connections of gender, gender expressions, the policing of gender, desire, sexuality. The book includes a glossary explaining key terms and all in all, seems like a good book for varied audiences.

4th of June – Celebrating Queer Literature

Each year I go through the Lambda Literary Award’s nomination lists and find plenty of books I need to add to my ever-growing wishlist. The award, which nowadays includes 22 different categories, aims to celebrate books which focus on LGBTQ themes and announced its winners at the 4th of June. The award covers everything from academic books to genre fiction. The way these categories are broken down along identity is at times debatable (as is some of the nomination and judging processes), but still it is an important showcase of LGBTIQ publishing. This year, I was particularly happy that Imani Perry’s immaculate biography Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry won best LGBTQ Non-Fiction. The award also reminded me of two books I had already on my radar but not yet on my shelves (a fact I set out to rectify): Disoriental by Négar Djavadi (won Bisexual Fiction) and As You Like It: The Gerald Kraak Anthology Volume II by The Other Foundation/ Jacana Media (won LGBTQ Anthology).

6th of June – Mother Tongue

(Ocean Vuong On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous)

But what if the mother tongue is stunted? What if that tongue is not only the symbol of a void, but is itself a void, what if the tongue is cut out? Can one take pleasure in loss without losing oneself entirely? The Vietnamese I own is the one you gave me, the one whose diction and syntax reach only the second-grade level. As a girl, you watched, from a banana grove, your schoolhouse collapse after an American napalm raid. At five, you never stepped into a classroom again. Our mother tongue, then, is no mother at all – but an orphan. Our Vietnamese a time capsule, a mark of where your education ended, ashed. Ma, to speak in our mother tongue is to speak only partially in Vietnamese, but entirely in war.

I was reading this one slowly – mostly because I kept rereading entire paragraphs due to their utter beauty. Vuong knows how to handle a sharp knife and set very precise incisions, cutting to the bone.

9th of June – Sista! Anthology

(Sista!: An Anthology of Writing By and About Same Gender Loving Women of African/Caribbean Descent with a UK Connection, Phyll Opoku-Gyimah, Rikki Beadle-Blair, John R. Gordon)

I finally grabbed the first anthology from my reading pile. Sista! has also been nominated for a Lambda Literary Award but I had acquired it even before. The anthology covers fiction and non-fiction as well as prose and poetry. The texts span personal experiences and documentation of community building and queer history. In the introduction the editors wrote:

[Y]ou will find poems of love and desire, longing and loss, trauma and triumph, of biological family and found/ claimed family; autobiographical pieces sharing both difficulties and the joy and power to be found in overcoming them; histories personal, social and political; tales of love from both elders/ foremothers and up-and-coming youth; affirmations of carefree singledom, loving coupledom and community; and lively, page-turning tales with women-loving black female protaginists at their centres.

This variety in themes and approaches makes the anthology to an important document – especially regarding the scarcity of such anthologies (as is also discussed in the introduction). As often with anthologies, I did not connect with all texts equally and some writing styles I preferred much over others. One of my favourite texts within the collection was Clementine Burnley’s short story “Forty Flavors”. (I absolutely love her writing. One of my favourite pieces, which is even more recent is “Lebensentwürfe” – German title but English text – which was published online last month.)

10th of June – When Nature Was Queer

(Mary Oliver Upstream, Hugh Ryan When Brooklyn Was Queer)

If this was lost, let us all be lost always. The beech leaves were just slipping their copper coats; pale green and quivering they arrived into the year. My heart, and opened again. The water pushed against my effort, then its glassy permission to step ahead touched my ankles. The sense of going toward the source.

I do not think that I ever, in fact, returned home.

Since the poet Mary Oliver passed away early this year I have been reading (and re-reading) my way through her corpus. Upstream is an essay collection in which Oliver brings her way of describing nature and her relationship to nature from poetry to prose – while this prose still reads like poetry. I read a few of the texts from the collection so far but the opening piece which shares the title with the entire book is my favourite still.

I also finished reading Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer and everything I said before about his carefulness was also true for the rest of the book. In this meticulously researched and engagingly written non-fiction monography, Ryan traces queer lives, experiences, and communities in Brooklyn from 1855 (the year Walt Whitman published Leaves of Grass) until 1969. He uses this focus to delve into a wide array of topics and themes, while always managing to hold all the threads together. He analyzes how ideas around gender and sexuality changed, writes about the architectural, social, and economic changes in Brooklyn and how the affected queer people in particular and delves into the history of performing arts and literature. He portrays a wide array of individuals – some famous, others not. Every page of this book is full of insights and interesting material. I appreciated Ryan’s precise analyses. He never tries to put people into neat boxes but rather describes their lives and contexts in detail, notes open questions or things we might never know, and also shows awareness of the contexts in which certain information was gathered (and why the wealth of material we have on groups of people varies). Going in, I was afraid this book might be overwhelming about white gay men (or what we might classify today as such) but this is not the case at all. Ryan is very much aware of gender, race, class, and makes a lot of effort to especially showcase the lives of those whose histories are rendered even more invisible than others.

In the minds of many, queer American history is a straight line forever shooting upward, a march of incremental progress, where decades of closeted anger finally explodes into public view on the first night of the Stonewall Riots of June 28, 1969. The truth is much more complicated. What we know of as being ‘gay,’ ‘lesbian,’ ‘bisexual,’ or ‘transgender’ didn’t exist until the early twentieth century, but there was still a strong presence of men who loved men, women who loved women, and gender outlaws of all kinds.

11th of June – In At The Deep End

(Kate Davies In At The Deep End)

I picked up In At The Deep End because I craved another ‘lighter’ read and sure enough I stayed up longer to finish reading because it is such a page-turner. But in the end, I wasn’t too sure how to feel about the novel. The book is about Julia a young woman living in London, working as a civil servant in a dead-end kind of job, and realizing that she is queer. In the beginning, the tone of the novel is light and funny and it is indeed entertaining to follow Julia stumbling around trying to figure out who she wants to be. But then she enters a relationship which can be only described as abusive. The contrast between the novel’s tone and the portrayed story is at times daring. I felt like the novel was supposed to do very different things at the same time and it not always worked out.

13th of June – Question of Canonisation

On Instagram, a group of fantastic queer bookstagramers banded together and created the hashtag #TakePrideInReading for June. Under this hashtag, they created a couple of prompts to start conversations about queer literature. This week’s prompt was all about ‘community classics’ (and underappreciated classics) and it made me think about the concept of ‘classics’. It’s so intertwined with canonisation which itself is deeply connected to eurocentrism, heteronormativity, classism, sexism, etc. Of course, in the last couple of decades, a lot of projects have been undertaken to decolonize an existing canon, to reinstate contrasting canons, to question the canon. But still: Isn’t the idea of a canon itself tainted with all these power imbalances and normative ideas. I also thought about a sentence I read in Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer:

[Q]ueer history has always been piecemeal and canonless […].

14th of June – At the Pool

(Casey Plett Little Fish, Jayrôme Robinet Mein Weg von einer weißen Frau zu einem jungen Mann mit Migrationshintergrund)

Summer really came through and it was hot in Berlin. I spent Saturday morning at the public pool alternating between dipping into the cold water and into two books I brought: Casey Plett’s novel Little Fish and Jayrôme Robinet’s memoir. Two very different books regarding genre, tone, and style but they have in common their focus on the lives of trans people thirty and older.

16th of June – Queering Migration Stories; Migrating Queer Stories

(Ocean Vuong On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Nicole Dennis-Benn Patsy)

What were we before we were we? We must’ve been standing by the shoulder of a dirt road while the city burned. We must’ve been disappearing, like we are now.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous takes the form of a long, winding letter from the protagonist, a young gay Vietnamese-American man, to his mother. But Little Dog, how his grandmother always calls him, writes in the knowledge that his illiterate mother might never actually read the text – a fact which liberates him. Vuong has crafted a remarkable novel with an emotional rhythm, beautiful sentence after sentence, and a lot to say. This is a novel about the long-term repercussions of the Vietnam war, inter-generational trauma, migration, a queer coming-of-age, loss and grief, drug abuse and the Opioid crises – but also about tenderness and love in many forms. The novel breaks open the often narrow boxes of ‘migration novel’ or ‘queer novel’. It is a novel ‘about’ many things but it isn’t one to just tick boxes. Instead, the book dissects questions of writing, memory, narrative, language, and silence. The result is a gripping, emotionally and intellectually multi-layered book.

Ocean Vuong’s book deals with queerness and migration but not as separate entities rather in their entanglements. In June Nicole Dennis-Benn’s second novel Patsy was published too. Another novel – with a very different tone, style, and story – which intertwines experiences of queerness and migration. I did not manage to finish her novel in June but I am sure to look at both at these books together might be a fruitful undertaking.

17th of June – Poetry and Pulp

(Gala Mukomolova Without Protection, Robin Talley Pulp)

Not all ghosts mean trouble —you could let her stay. (To aid sleep, recite the Cyrillic alphabet.)

I love poetry – and most of my favourite poets are also LGBTQ writers, though somehow only one poetry collection made my June reading stack. Though at least the one collection I read – Gala Mukomolova’s Without Protection – was wonderful. Mukomolova writes poems drawing from Russian folklore (finally again a book referencing Baba Yaga I loved), migrant experiences, Jewish influences, and queerness. There are craigslist ads and fairytales and everything in between.

Then I also read a YA novel by Robin Talley. Actually the third book of her I have read over the last couple of years and while I didn’t dislike Pulp (actually there was a lot about the book I enjoyed) it also once again showed me that while I am excited about Talley’s premises she is not the author delivering for me.

Pulp book is about Abby. She is a high school senior and desperate to find a senior year project. For the life of her, she does not want to think about college applications. Her parents do everything to not be at the home at the same time. Abby and her girlfriend have taken a break some time ago and now the question remains if getting back together is what either of them wants. So in the mids of all that Abby discovers lesbian pulp fiction from the 1950s and an obsession begins. Pulp alternates chapters between Abby and the story of Jane, a young lesbian girl in the 1950s who – in the middle of the McCarthy era – writes one of the pulp novels Abby falls in love with decades later.

I actually liked both storylines even though Abby was a bit obnoxious at times and I enjoyed how Talley alluded to concrete political and historical events and realities as well as including a lot about lesbian pulp fiction its history, tropes and authors (she references a lot of actual books and gives a reading list at the end). But, there is this thing that Talley is very aware of the need to have a diverse cast and to acknowledge different experiences but – for me – never gets it quite right. Past books of her I found actually really bad in this regard (at times deeply problematic), Pulp has its problems too. Both main characters are white cis lesbians but there are many BPoC and trans characters. The problem? They are barely developed; they exist either to plainly signify a diverse cast or to help the protagonists learn (a complicated, racialized dynamic). In the end, I sped through these 400 pages and was entertained – but decided to let that be the end of me picking up Robin Talley’s novels.

20th of June – Little Fish

(Casey Plett Little Fish)

Wendy wanted to love this old woman. She was so, so tired of loving her people and them not loving her back. Sometimes this made her angry. And sometimes, like now, she found it spookily easy to put her hurt and baggage on ice.

I finished reading Casey Plett’s novel Little Fish. A book about thirty-year-old trans woman Wendy who after her grandmother’s death receives a phone call which implies that maybe her devout Mennonite farmer grandfather – who had been dead for a while already – has also been trans. Plett shows how Wendy grapples with this possibility but also shows her daily struggles, her friendships (mainly with a group of other trans women), and her complex relationship with her father. The novel deals with issues such as religion, suicide, alcoholism, the health care system, sex work and other paid work but without it ever feeling like all these things are just thrown in. Plett’s characters felt very real and their lives too.

21st of June – Sara Ahmed’s Queer Ear for Queer Peer

Mere persistence can be an act of disobedience. And then: you have to persist in being disobedient. And then: to exist is disobedient.

Sara Ahmed’s Living a Feminist Life is one of my favourite books. Sometimes I just open a random page and read and there is always something speaking to me. So when I realized she was speaking in Berlin as part of the festival The Present Is Not Enough – Performing Queer Histories and Futures I was delighted to get one of the last tickets. Ahmed gave a talk titled “Mind the Gap! Complaint as a Queer Method” and it was as inspiring as anticipated. She spoke about the ways complaints lay open power structures, can be methods for change (but often also show how institutions do everything for complaints to not actually have an impact), and how we find other people with shared experiences and politics via complaints. A lot of her research about complaints is based on interviews, a method Ahmed described as “not queer eye for the straight guy, but queer ear for the queer peer”. In October her newest book, What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use, will be published!

22nd of June – Queer Anthologies

(Elisa Barth et.al. (eds.) Inter: Erfahrungen intergeschlechtlicher Menschen in der Welt der zwei Geschlechter, Phyll Opoku-Gyimah et.al. (eds.) Sista!: An Anthology of Writings by Same Gender Loving Women of African/ Caribbean Descent with a UK Connection, Love Is Love: A Comic Book Anthology to Benefit the Survivors of the Orlando Pulse Shooting, Jacana Media (ed.) As You Like It: The Gerald Kraak Anthology African Perspectives on Gender, Social Justice and Sexuality)

Reading allows me to be part of something, a community, even though I am almost always physically alone. Usually in bed. Some days the longest amount of time I spend out of bed is the thirty minutes it takes to eat something and assure everyone in the vicinity that I am completely alive and okay. (Efemia Chela)

Over the month of June, I read four anthologies – two I have already written about above. For me, a good anthology brings together different voices and approaches. In the best case after having finished an anthology, I found a couple of writers or artists I had not known prior. Also in the best anthologies, the pieces within speak to each other and create something more than the sum of the individual pieces (no matter how trite that turn of phrase). My absolute favourite anthology I read in June was As You Like It: The Gerald Kraak Anthology African Perspectives on Gender, Social Justice and Sexuality which had won the Lambda Award for best LGBTQ Anthology. This anthology – which represents shortlisted works for the Gerald Kraak award – includes memoiristic essays, literary critique, fiction, poetry, reportage, and photography. There are works such as Pwaangulongii Daoud’s fantastic essay (and winner of the Gerald Kraak price) “Africa’s future has not space for stupid black men”, Efemia Chela’s reading of Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, beautiful poems about love and (be)longing and much more by Sarah Lubala, and Siphumeze Khundayi’s and Tiffany Mugo’s photo essay “‘Your kink is not my kink’ African queer women and gender non-conforming persons find sexual freedom in bondage”. The opening text by Isaac Otidi Amuke (“Facing the Meditteranean”) is a well-researched and carefully narrated reportage about LGBTQ refugees from Uganda and LGBTQ people remaining in Uganda, which ends on the following note:

[I]n the middle of all this, the UNHCR, the NGOs, and the complex system designed to facilitate asylum are clearly struggeling to understand that many things can be true at the same time; that in fact home may tolerate you, but if it also forces you to negotiate your full humanity, then you’d rather live in limbo, in a camp somehwere, holding out for what is possible.

The most uneven anthology I read this month was Love Is Love: A Comic Book Anthology to Benefit the Survivors of the Orlando Pulse Shooting. While this anthology was put together for a good cause and the proceeds are donated, the title (Love is Love) is already a good indicator to the framing (starting with a strange comparison between the Orlando shooter and Aileen Wuornos) and the gaze of the book. There are some fantastic pieces – mostly by (BPoC) LGBTQ artists – in the anthology but they are at times a bit lost between comics about cis straight people’s feelings and stories (often about how they tell their children that “love is love”).

24th of June – Memoirs

(Nishta J. Mehra Brown White Black: An American Family at the Intersection of Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Religion, Jayrôme C. Robinet Mein Weg von einer weißen Frau zu einem jungen Mann mit Migrationshintergrund, Cherríe Moraga Native Country of the Heart)

Besides anthologies, I also read a few memoirs: I finished reading two (Nishta J. Mehra’s book I read during the first June weekend and Jayrôme C. Robinet’s memoir) and read parts of another one (Cherríe Moraga Native Country of the Heart). For me, a great memoir not only documents life experiences but offers reflections, meditations on different topics, sometimes open questions. I enjoy memoirs which not only offer an interesting story but also evocative writing (my favourite (and also queer) memoir so far this year: T Kira Madden’s Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls). Mehra – as described above – and Robinet have delivered thematic and stylistically interesting books. Robinet writes about his transition and the anticipated and not anticipated changes in his body, his relationships, and the ways the world understands him. One of the interesting shifts he describes is how after being seen as a white woman he is suddenly read as a young male migrant (whereas ‘migrant’ does not mean French). A thought-provoking book with a few aspects I wish were dealt with differently though.

26th of June – Fictional LGBTQ Role Models

Over at Mädchenmannschaft, we published (in German) a new episode of our series and film podcast Bury Your Gaze. In the episode, Nadine Lantzsch and I talked about LGBTQ characters in recent series we admire for one thing or another. And while there is still so much to do with regards to representation and the variety of stories which are told – and with regards to who gets to write, act, produce, direct these stories -, I did marvel at the multitude of series we could choose from. (We spoke about Emma Hernandez (Vida), Clare Devlin (Derry Girls), Blanca & Pray Tell (Pose), Elena Alvarez (One Day at a Time), Anne Lister (Gentleman Jack), and The Princess Alliance (She-Ra and the Princesses of Power).)

27th of June – Performing trauma?

Reading the memoirs mentioned above but also discussions around some of the novels I, once again, got into thinking about the ways marginalized people are often expected to write memoirs – or even if they do write fiction it is solely read as autobiographical; the way marginalized people are asked to perform their trauma for a majority society. This question was also prominent in Travis Alabanza’s performance Burgerz which I saw as part of the The Present is not Enough festival too. Alabanza speaks about an attack in which Alabanza was hit by a burger in broad daylight and no one acted supportively. The burger becomes a starting point for explorations of the gender binary and how it is upheld (including its colonial history). But Alabanza also broaches the issue of performing trauma (and for who and with which effect) directly engaging the audience. A troubling – in the best sense – performance.

28th – 30th of June – The Queer Women And The Sea

(Meredith Russo Birthday, Kirsty Logan The Gloaming, Michelle Tea Girl at the Bottom of the Sea, New York Public Library (ed.) The Stonewall Reader)

This last June weekend was the best. On Friday I left Berlin and travelled to the North Sea meeting up with (almost all) members of the feminist collective I am glad to be able to call my political, intellectual, and emotional home. These are the people who help me make sense of this world (I can’t even start to count how much I learned from each and everyone involved) but they are also the funniest people I know. So, knowing all of that I have no idea why I packed so overambitiously in the book department: I thought I might finish two books which deal with the sea (last year when we went together to the North Sea I read Tove Jansson’s Fairplay – so I could have started a tradition with reading queer women’s narratives about the sea at the sea…). Kirsty Logan’s The Gloaming and Michelle Tea’s Girl a the Bottom of the Sea are both books about queer girls/ women and mermaids – though very different tales. I loved all of Logan’s previous books and I really enjoyed Tea’s first book in the series, but over this way too short weekend I read only a few chapters in each book.

But I read something: On the train ride on Friday, I read the entirety of Meredith Russo’s second YA novel Birthday. In this novel, we meet the protagonists Morgan and Eric on their 13th birthday celebrating in a waterpark. These two have been best friends forever and Morgan thinks about revealing something important: she is a girl and not a boy as everyone assumes. Birthday is a love story as the tagline of the cover already points out. However, this YA novel is not so much about the endpoint (though of course, this portrayal of love is important too) but about the journey. The book is set on six days only: Morgan’s and Eric’s birthdays from 13 to 18. Through these snapshots of their lives, Russo traces both of their coming into their own, their ups and (crushing) downs. Both have a lot on their plate: Morgan tries to accept herself as a trans girl while she is constantly bullied by homophobes and has to deal with the death of her mother (which happened before the book starts) and her grieving, often half absent football coach father. Eric is the youngest of three sons constantly under scrutiny to perform masculinity in the ‘right way’ by his abusive father. Morgan and Eric are so very tender souls (in alternating chapters the reader gets both perspectives) and their relationship over the years is beautiful if not conflict-free. They are complex characters and their personalities and interests are not linked in a cliched way to their genders. I felt that some of the other characters could have fleshed out a bit more and a few problems were resolved quite quickly at the end. But these are minor points, all in all, a great multi-layered novel.

On my way home, I finally (and very fittingly) finished The Stonewall Reader which I had started reading earlier in June. The book is split into three parts: before, during, and after Stonewall. Each section consists of excerpts from books (memoirs, novels etc), other short texts, and interviews. I really did like the ‘During Stonewall’ section which put together a lot of different, at times contradicting accounts (including Interviews with Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera) and which ends with a very interesting, retrospective interview with Miss Major Griffin-Gracy. It is a fascinating collection of material, though I think the introduction could have been a bit longer, more detailed and more critical in its approach. But it felt right to end June with The Stonewall Reader which not only sheds some light on queer history but also reminds you how messy memory, activism, resistance, identities, and lives are. How messy, and how gloriously defiant.

One Comment

Pingback: