Contemporary Queer Nigerian Writing

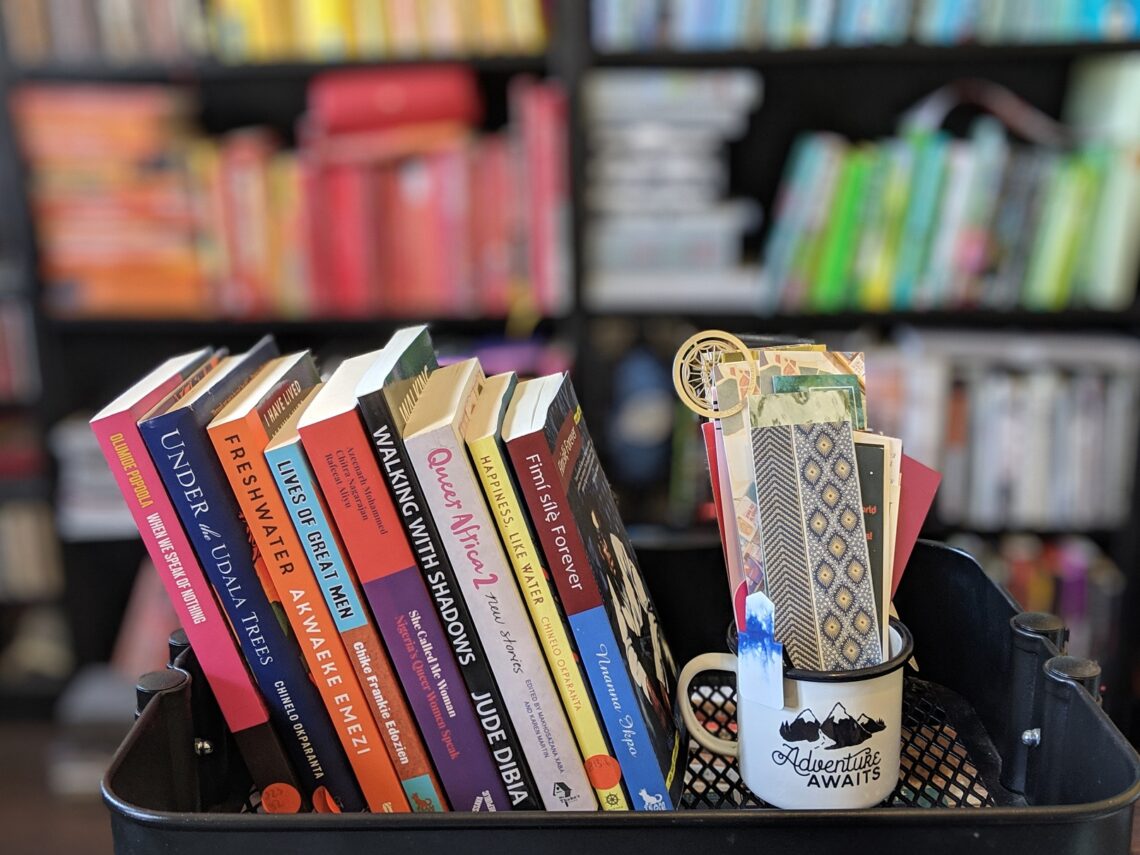

Over the last couple of years, I accumulated a fair amount of books (texts) from Nigeria/ by Nigerian and Nigerian diasporic authors which tackle queer themes and focus on LGBT+ protagonists. This list brings them together in one post. It is not to supposed to be a complete representation of everything ever published. I left out short stories (for examples those included in the Queer Africa short story collections, but also from writers like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie or Chinelo Okparanta – whose novel is part of the list) and books which only have minor queer characters. Also, I still do not own Unoma Azuah’s BLESSED BODY: The Secret Lives of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Nigerians (2017) but I think it is important to mention as part of the rather slim corpus of non-fiction. I also highly recommend Safe House: Explorations in Creative Non-Fiction edited by Ellah Wakatama Allfrey in which the experiences of LGBT+ people in different African countries are featured several times and which includes a wonderful essay by Elnathan John called “The Keepers of Secrets” about Northern Nigeria. And of course, neither ‘queer’ (and thus ‘queer writing’) nor ‘Nigerian’ (and thus ‘Nigerian writing’) are clear categories but that is not the topic today.

Fiction

Jude Dibia Walking with Shadows (2006): This is the often-quoted first Nigerian novel which centres on a gay protagonist. Dibia tells the story of Ebele (Adrian) Njoko, a married father, who has to deal with the aftermath of a forced outing. Dibia portrays how his protagonist – and

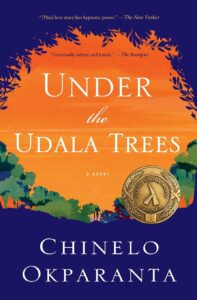

Chinelo Okperanto Under the Udala Trees (2015): Almost ten years after Dibia’s novel, Okperanto published her debut novel. The Biafran war is raging, when Ijeoma, an Igbo girl, falls in love with Amina, a Hausa orphan. Their love is a transgression on many levels and when their relationship is discovered, Ijeoma the two girls are separated. Okperanto than follows Ijeoma for the coming decades and portrays not only coming-of-age but also coming into her own against multiple obstacles. She shows Ijeomas complex examination of (her) faith and Christian beliefs, her relationship with her mother, and how she carves out her own way between denial and joy. Published in the wake of Nigeria’s 2014 anti-LGBT bill, this novel inscribes queer characters into Nigeria’s recent history and maintains their existence and importance. While I found some parts a little bit too didactic, the writing a taint too lost in descriptions, I loved how Okperanto not only shed light on Ijeoma’s story but also showed queer communities and more than one queer relationship and thus does not paint Ijeoma’s story as a singular and isolated one. Chinelo Okperanto’s 2013 stunning short story collection Happiness Like Water includes also stories about queer characters. (I did enjoy the short story collection more than the novel.)

Nnanna Ikpo Fimí Sílẹ̀ Forever (2017): This is the only book on the list I have not finished yet but I am in the middle of it and really enjoy it so far. Ikpo writes about Olawale and Oluwole, two brothers – twins – who are both lawyers and bi. But besides this resemblance the two are very different, they differ in character and also in how easily they are read as straight. So far, it’s a fascinating story about family, secrets, live in Nigeria after the Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act became law, activism, and creating art. The story is pitched in the following way: “Fimí sílẹ̀ Forever celebrates the enduring power of love, desire, faith, patriotism and human rights struggle in the face of political oppression and religious prejudice in Nigeria today. It extends the literary conversation begun by Jude Dibia and continued by Chinelo Okparanta. “

Olumide Popoola When We Speak of Nothing (2017): After her novella, this is not about sadness (2010) about the friendship of an older Jamaican woman and a younger South African one, Popoola published this novel which again focusses on friendship and at least one queer character, though that is where the similarities stop. Karl and Abu are both 17, best friends, and live in London. It is 2011 and political/ social tension lies in the air. When Karl suddenly has the opportunity to meet his father in Nigeria, he takes the chance and leaves Abu behind. Popoola wrote a beautiful novel about growing up, making decisions, friendship, and masculinities; touching upon the ‘London riots’, questions of oil in the Nigerian delta, and Karl’s experiences as a trans boy in UK and Nigeria. Popoola invents a wonderful narrative voice, employing Esu the Yoruba deity, guardian of crossroads, and the constant flow of texting at the same time. Content and form make up a wonderful multi-layered work.

Uzodinma Iweala Speak No Evil (2018): Iweala could be described as a pretty topical or “issue” writer (his first novel, Beasts of No Nation (2005), has been about child soldiers) but that would do a disservice to his craft. Iweala definitely knows how to write. In his second novel, he tells the story of Niru a high school senior living in Washington, D.C. with his Nigerian parents. He is a good student, already admitted to Harvard, and a star of his track team. When he tells his best friend Meredith that he is gay gradually things take a turn for the worst. And when his father discovers that Niru is gay the fallout is horrible. Iweala not only tackles a coming-out and first love story but also topics such as homophobia, conversion discourses, domestic violence, toxic friendships, white privilege, and police violence. All important themes, and all worthy of a good novel. Unfortunately, Speak No Evil did not entirely work for me. The writing is good, but the characters rarely exist outside of their roles in each of these conflicted constellations. The book is a classic tragic queer story which ends with a shift of perspectives centring on the straight characters and their feelings. The story is not only gloom, but the lighter moments are few and between and only make the decline even harsher.

Akwaeke Emezi Freshwater (2018): Emezi’s debut novel is definitely something else, masterfully shifting perspectives and leaving the reader with a fragmented narration to piece together. Freshwater follows Ada from birth into adulthood. Ada is the answer to her parent’s prayers, who wished for a girl but got more than they bargained for: Ada is an ogbanje. As Emezi writes in their essay at The Cut: “An ogbanje is an Igbo spirit that’s born into a human body, a kind of malevolent trickster, whose goal is to torment the human mother by dying unexpectedly only to return in the next child and do it all over again. They come and go.” The spirits in Ada come – but they don’t go and instead, she grows up and the spirits are stuck in a human shell, their brothersisters angry about their staying away. Experiencing a row of violent, traumatic events, Ada struggles to cope and with the spirits within her, which manifest in more solid forms over time. Emezi’s lyrical writing shifts between the spirit ‘we’, Ada, and specific spirit manifestations. Through these perspectives Ada’s at times harrowing life is told; there is abuse, sexual violence, loss, mental health issues, heartbreak, spiritual dilemma, a suicide attempt. This is hard to stomach, even though the narration is often a bit detached since the spirits have only limited empathy for human life. Freshwater though does not end without hope. It is a book about all the aforementioned topics, but at its core, it is about a spiritual journey as well. Emezi also manages to rope in a portrayal of desire and gender deeply intertwined with Ada’s ogbanje identity thus transcending Western cisheteronormative models. As the spirit we puts it: “We understood what we are, the places we are suspended in, between the inaccurate concepts of male and female (…).” Emezi’s new book will be out this year: a YA novel, Pet, featuring a trans girl as the protagonist!

Non Fiction

Pwaangulongii Dauod “Africa’s Future Has No Space For Stupid Black Man” (2016): Daoud’s seminal essay was published by Granta and you can still read it online. A non-fiction must read about community and the effects of always living in fear.

If you were in this hall, you would feel how we assert ourselves through music, words, dance, hair, fashion, technology, ideas and spirits. We are spirits. If you were here, you would notice that we are not the demons roaming your cities and villages with evil and sin in our bosoms. We are not wayward, perverse, queer or funny lovers. We are children of our parents, children of this continent, children of nature, of imagination and of hunger. If you were in this club seeing the tears roll down our eyes, feeling the sweat on our bodies, pouring down our torsos to our pants, as we move to Afrobeat, Afropop, highlife and juju, you would realise that WE ARE CHILDREN OF OUR GODS. We exist.

Pwaangulongii Dauod

Chike Frankie Edozien Lives of Great Men: Living and Loving as an African Gay Man (2017): Edozien is a journalist and professor of journalism based in the USA. In this memoirs, he writes about growing up gay in Nigeria, his experiences in the USA, France, Ghana, South Africa, and some other countries – and the gay/ bi African men he meets everywhere. Edozien delves into his relationship with his family and his father in particular, his immigration story and experiences as a journalist in the USA, and the lives of the men he loves, admires, and sometimes resents. He brings together his more personal anacedotes and wider observations. He also includes one chapter in which he focusses on the experiences of queer women in Lagos – though, for me, it was weaker then the rest of the book. One could feel the distance and the analysis were a bit lacking. All in all, this is a fascinating read which is written in a compelling way. I flew through it and will surely return to it at some point.

Azeenarh Mohammed, Chitra Nagarajan, Aisha Salau She Called Me Woman (2018): Published last year, this is such an important addition to the corpus. This book collects the stories of queer people in Nigeria with a clear focus on women. The texts do not try to show a specific picture or only reflect easily palatable stories, instead, the vignettes seem not to be edited heavily in style and content (which at times makes reading a bit bumpy) and portray a variety of experiences. A huge strength of the collection is the variety of stories which represent different age groups, people in cities and more rural areas. The introductory essay by the editors gives context to the included life stories and explains very well the approach, aims, and boundaries of the book. Last year, I was lucky enough to interview one of the editors – you can read the conversation over at Mädchenmannschaft.