Guide: Books on Disability/ Chronic Illnesses/ Neurodiversity/ etc.

This is a living list with works which deal with disability and/ or chronical illness and/or Deafness and/or neurodiversity and/or mental illness and more. It’s about disability rights and movements, about ableism, about survival and solidarity, about pain and grief, and about joy and care. A lot of the descriptions here are taken from reviews I have shared on Instagram and thus vary in style, length and approach. Obviously, this list is not complete as it only reflects my reading (and only what I remember I have read). Nonetheless, I hope this list ist helpful.

“Disability is adaptive, interconnected, tenacious, voracious, slutty, silent,

raging, life giving” ‑ Leah Lakshmi Piepzna‑Samarasinha

“You can feel sad and create a meaningful, joyful life.” – Tessa Miller

[Last updated: 3rd of December, 2024]

Non-Fiction

Raúl Aguayo-Krauthausen: Wer Inklusion will, findet einen Weg. Wer sie nicht will, findet Ausreden. (2023)

German book on disability and inclusion. I think this is a pretty good, accessible primer for people starting to engage with the topic. Aguayo-Krauthausen does not only built on his own experiences and expertise but also interviewed several people with different backgrounds and experiences to create a more nuanced and layered picture.

Cece Bell: El Deafo (2014)

Cece starts a new school. Something which would be scary to most but is especially scary to her as – in contrast to her old school – no fellow student knows her yet and thus don’t know that she is deaf. She feels in particular selfconscious about the Phonic Ear she wears to be able to understand her teachers in class – but when she realizes wuth the Phonic Ear she can not only hear her teacher in the classroom but also when they are out and about in elsewhere in the school, a new super power is unlocked. This is a really wonderful MG graphic memoir about friendship and coming into one’s own.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore: The Freezer Door (2020)

You’d think they would have fixed the pavement before installing those rainbow crosswalks, but I guess the cracks make everything more realistic. Each rainbow crosswalk cost $6000, so you know they used good paint. And one of the crosswalks leads right to the police station. An imagined community is one way to describe heartbreak.

In “The Freezer Door”, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore wanders through Seattle always on the lookout for connections – through conversations, cruising, looking. This book has a sadness embedded in it as she reflects on desire, queerness, grief, sickness, and gentrification. But there are also pockets of joy and moments of pure humour or slightly probing absurdism.

Not every paragraph hits the same way, some seem a bit overwrought others had less substance than they pretended to have. But then again there are sentences which make you pause and fell them through and through like when Bernstein Sycamore assess: “When someone says the body never lies, I wonder if they’ve ever had a body.”

That Maggie Nelson blurbed this book just makes sense: If you love her kind of queer, reflective, associative, fragmented writing, you will also enjoy The Freezer Door.

Selma Blair: Mean Baby: A Memoir of Growing Up (2022)

Review upcoming.

Anne Boyer: The Undying: A Mediation on Modern Illness (2019)

Anne Boyer looks at literary representation, medical history and discourses, the ways (capitalist) societies treat the ill. She writes about the very physical bodily realities of illness as well as about all the thoughts going through one’s mind living through life threatning illness. The Undying is deeply intimate while opening up contexts. It is heartwrenching (ad infuriating) to read about Boyer forcing herself to work in the midst of treatment and shortly after her mastectomy. There are other parts I will reread as they have been masterfully crafted and open up so many lines of thought.

Keah Brown: The Pretty One: On Life, Pop Culture, Disability, And Other Reasons To Fall In Love With Me (2019)

The Pretty One is the debut essay collection of Keah Brown (who started the Twitter hashtag #DisabledAndCute). In these essays she writes about her love for pop culture, feelings of jealousy and the complex relationship with her twin sister, questions of representation, the ways society is neither built for Black nor disabled people, the power of friendships, and the longing for romantic love, and also living through episodes of suicidal ideation.

Brown has a wonderful way of looking back with honesty and kindness onto her past thoughts and actions and locating them within the context of a racist, ableist, sexist society. Her writing is funny, tender, and straightforward.

Going in I already anticipated that her style won’t be my favourite kind of writing style and that proofed partially to be true (but then again I knew that and was here for her perspective). I do think though that some essays could have been edited down slightly and made a bit sharper. Also sometimes I wished for more depth – but may be that was just me wishing for another kind of essay and that is more on me and my preferences than on the book.

The essay which stayed most with me was surprisingly (as I was not so interested going in) Browns Essay about love and especially the lack of romantic love and her experience of not feeling/ being desired.

Alina Buschmann, Luisa L’Audace (eds.): Angry Cripples: Stimmen Behinderter Stimmen Gegen Ableismus (2023)

“Behinderte Menschen, die nicht die Rolle der ständig dankbaren und bescheidenen Personen annehmen, laufen schnell Gefahr, als verbittert abgetan und als “Angry Cripples” bezeichnet werden. Wir holen uns den Begriff zurück. Wir sind laut, wir sind wütend und wir haben verdammt nochmal das Recht dazu,” schreiben Aline Buschmann und Luisa L’Audace in der Einleitung zur Anthologie Angry Cripples: Stimmen Behinderter Menschen gegen Ableismus.

Das Buch bringt zusammen Essays, Interviews und visuelle Kunst. Alle Autor*innen und Künstler*innen wenden sich verschiedenen Themen zu und leben mit verschiedenen Behinderungen (und anderen Marginalisierungserfahrungen). So entsteht ein komplexes Bild von gelebten Realitäten behinderter Menschen – ergänzt noch durch Zitate weiterer Personen im Mittelteil, der suggeriert: Hier kann immer nur ein Ausschnitt abgebildet werden.

Viele der Beiträge werden mir in Erinnerung bleiben: So schreibt zum Beispiel Natalie Dedreux als eine Person mit Down Syndrom über die Diskussionen und Praxen rund um Pränataldiagnostik. Jasmin Dickerson hat einen berührenden Text über Einsamkeit als behinderte Person und Mutter eines ebenfalls behinderten Kinds geschrieben. Es geht auch um das Schulsystem, die Rolle als behinderte Influencerin, Behindertenwerkstätte, internalisierten Ableismus und die Klimabewegung.

In der Einleitung heißt es, dass Erfahrungen/ kreative Inhalte behinderter Menschen ausschließlich auf Social Media stattfänden und man sie in Büchern oft vergeblich suche. Ich finde es sinnvoll auf die besondere Rolle von Social Media hinzuweisen, aber hätte mich auch über etwas mehr historische Anbindung an der Stelle gefreut: denn natürlich haben behinderte Menschen bereits vor Social Media Dinge produziert – und es gibt auch andere Bücher (wenn auch natürlich es noch viel mehr geben soll!).

Eli Clare: Exile and Pride. Disability, Queerness, and Liberation (1999)

The mountain as metaphor looms large in the lives of marginalized people, people whose bones get crushed in the grind of capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy. How many of us have struggled up the mountain, measured ourselves against it, failed up there, lived in its shadow? We’ve hit our heads on glass ceilings, tried to climb the class ladder, lost fights against assimilation, scrambled toward that phantom called normality.

We hear from the summit that the world is grand from up there, that we live down here at the bottom because we are lazy, stupid, weak, and ugly. We decide to climb that mountain, or make a pact that our children will climb it. The climbing turns out to be unimaginably difficult. We are afraid; every time we look ahead we can find nothing remotely familiar or comfortable. We lose the trail. Our wheelchairs get stuck. We speak the wrong languages with the wrong accents, wear the wrong clothes, carry our bodies the wrong ways, ask the wrong questions, love the wrong people.

Laura Kate Dale: Uncomfortable Labels ‑ My Life As A Gay Autistic Trans Woman (2019)

In this autobiography, Laura Kate Dale writes about her experiences as a gay, autistic trans woman. She writes that while quite a huge percentage of LGBTQ people are also autistic, it is rarely discussed together.

Anna Faroqhi: Krebs Kung Fu (2017)

Anna Faroqhi is a Berlin-based film maker and arist. In this German graphic memoir she reflects on her diagnosis with cancer and the subsequent treatment. She illustrates the sad moments as well as the absurd, the day-to-day. Faroqhi has a very distinct drawing style which was not my absolut favourite, but I am glad I read this.

Josie George: A Still Life: A Memoir (2019)

It is so easy to be boring. I can’t stress how much this sentence struck a chord with me being in the middle of another round of diagnoses. Being chronically ill is obviously not the only thing which characterizes me – not by far – but being chronically ill can be incredibly time-consuming. Talking to friends you feel like your only life updates are health related because it’s so overwhelming. But also kind of boring. This is not easy to navigate.

Josie George has been living with disabling chronicle illnesses for most of her life. Now she lives in a small house the Mid Westlands with her son. The radius of her life does often not exceed hundred meters. In “A Still Life” she chronicles her life for one year going through the seasons while also sharing stories from growing-up and general reflections. This is a beautiful quiet book about community, friendship, nature, disability, parenthood, and love. George discribes wonderfully honest and poetic ways to live life to the fullest – even if this looks different to what an ableist, capitalist society tells you your life should look like.

Start, stop a pattern had begun. It was me and I was it. A life of constant interruption, I would say, complaining. Whenever I would think myself free and clear of it, I would be brought to a stop again. Back then, I stopped each time I was stopped, waiting to live and try again, not knowing that this still time too was living, that this still time was more real, in fact, than those bright and unsustainable times of promise, laden with the temptation to run clear of myself.

UPDATED: Hafizah Augustus Geter: The Black Period: On Personhood, Race, And Origin (2022)

“I was trying to emerge from erasure.”

In The Black Period, Hafizah Augustus Geter asserts her place as a Black queer disabled woman born to a Muslim Nigerian mother and a Black American father from a Southern Bapitist family. Bringing together visual art, poetry, criticism, memoir and essay, Geter puts together a vivid image of intergenerational trauma, the effect of racism on Black bodies, structural violence, grief but also of community, art, joy and resistance.

“I say, ‘the Black Period,’ and mean ‘home’ in all its shapeshifting ways.”

There are so many fantastic paragraphs and pages in this book and it’s brimfull with references. I also found the structure, on the one hand, interesting and innovative, but, on the other hand, I sometimes wished for a bit more of an explicit red line throughout these more than 400 pages. I did feel a bit falling from scene to scene, thought to thought – though there is also something very appealing about that.

M. Leona Godin: There Plant Eyes. A Personal and Cultural History of Blindness (2021)

Godin offers a wild ride through history, texts from Homer to Dune, pop culture, and sciences. She analysis how blindness is portrayed, discussed, or reacted to; the ideas which are prominently displayed about blindness and the ways blindness is used a figure of speech. For example, she wades through classic texts such Sophocles’ Oedipus plays pointing out the functions of the figure of the “blind seer” – utterly fascinating. In the past, Godin has also produced theatrical performances. One of them being about Helen Keller’s time performing in vaudeville, so, of course, there is also an utterly interesting chapter on Keller.

UPDATED: Alexis Pauline Gumbs: Survival is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde (2024)

In the prologue of Survival Is A Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde, Alexis Pauline Gumbs describes their approach to the book:

This biography, twenty years after the first official textual biography of Audre Lorde, multiple biographical films, and a bio-anthology, needs not to wrestle with the fear that the world will not remember the name Audre Lorde. Her students and loves ones have been vigilant and they have prevailed. The question for us is whether we ourselves, the generations Audre made possible, will survive the multiple crises we face as a species largely detached from our only planet and ignorant about the universe that connects us. And this is why we need the depth of her life now as much as we ever have. We need her survical poetics besond the iconic version of her that has become useful for diversity-center walls and grant applications. We need the center of her life, the poetry that society at large has mostly ignored, preferrring to recylce the most quotable lines of her most quotable essays (necessary as those essays are!).

Based on Lorde’s poetry, other texts and a lot of archival material, Alexis Pauline Gumbs creates an unusual biography. The book does not just narrate Lorde’s life in a chronological order but rather focusses on themes. It is a book of tangents – in the best possible way. Alexis Pauline Gumbs especially looks at natural metaphors and imagery and dives deeper into these (in a way only they are able to and in a way which makes this biography very cleary their work). And by all the admiration for Lorde and her work, Gumbs also shares critical analyses. I am especially thankful that this quite hefty book has got a great index which allows one to go back to certain topics and read up on them.

UPDATED: Sofie Hagen: Will I Ever Have Sex Again? (2024)

In this book Hagen writes about sex and the lack thereof, desire and societal structures which influence desire and access to intimacy. They write about their very personal journey but also include stories of other people to cover a wider range of experiences. Among many other aspects, Hagen touches upon fatness, queerness, and disability.

Kathleen Hanna: Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk (2024)

Kathleen Hanna is best known as the front woman of iconic bands such as Bikini Kill and Le Tigre. In this memoir Hanna looks back at her tumultous childhood, her experiences with punk, grunge and riot grrl and all the other big topics of her life. She also writes about her life with Lyme disease.

UPDATED: Johanna Hedva: How to Tell When We Will Die: On Pain, Disability, and Doom (2024)

If you loved Hedva’s seminal essay “Sick Woman Theory”, you will love this collection. Hedva writes about concepts of disability within capitalism, about grief, about the doom of it all. They critically read works by writers such as Deborah Levy and Susan Sontag. It is also about kink, queer- and transness, the medical system, about class and racism, about activism, and so many other aspects. And they dive into the archetypes of The Psychotic Woman, The Freak, and The Hag. This is often thoughtprovoking, the writing poetic.

There are also aspects I would love to discuss, to expand on, to turn from side to side in my mind. I think it is always incredibly difficult to write about disability in a all-encompassing way as disability and chronic illness can take so many forms and describe so many very different experiences and and in some essays I feel the book fell into the trap of being a bit too generalizing when actually being tethered to Hedva’s specific experiences. But also these are essays in the truest meaning of the word, texts which try to ask more and new questions, texts which try. And I loved to read through this collection and will certainly return to some of these texts again and again.

John Hendrickson: Life on Delay: Making Peace with a Stutter (2023)

Hendrickson came into focus, when in 2019 he published a story for The Atlantic about Joe Biden’s stuttering. In Life on Delay, he now focusses on his very own experiences with stuttering. He writes about his family’s handling of his stuttering the repurcussions of that, he writes about bullying, depression and substance abuse, but he also writes about his career as a journalist.

I think this was the first book I read by someone writing about their experience with stuttering. I did learn quite a bit. But for me, the baseline of Hendrickson’s analyses was too liberal and too little informed by disability justice.

Judith Heumann (with Kristen Joiner): Being Heumann – An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist (2020)

Being Heumann is narratively a rather conventional autobiography telling about Heumann’s live chronological focusing on her most important activist achievements and ending with a chapter discussing how Trump’s administration dismantles many of the positive changes initiated over the decades. But following Heumann’s journey from her Brooklyn childhood born to two Jewish parents who had had both to flee Germany, her family’s fight to get her educated and Heumann’s first big strike: her lawsuit against the Board of Education of the City of New York is absolutely captivating.

Michele Lent Hirsch: Invisible: How Young Women with Serious Health Issues Navigate Work, Relationships, and the Pressure to Seem Just Fine (2018)

What a mouthful of a title, but it also captures quite well what Michele Lent Hirsch tries to tackle in 230 pages. She looks at a quite specific demographic: women, who have mostly “invisible” illnesses and (for the most part) only fell ill as (young) adults. The book is divided into six parts looking into (romantic and sexual) relationships, the work place, friendships/ social life, the medical system, parenthood, and media. Hirsch writes about her own experiences, but goes in her explorations far beyond these using a lot of interviews, other literature and studies. She attempts – very succesfully – to reflect a vast array of experiences in regards of class, sexuality, race etc.

A few stories which stuck: Hirsch interviewed a young trans woman of colour about friendship. The woman said she was afraid of not always being able to be a good friend (for example being an attentive listener), because she associates these traits (bad listener etc) with the men she witnessed growing up and feared her friends might see her as masculine. Another interviewee works in a lab studying HIV. She is the only Black woman on the job, which is already challenging enough but she also has to navigate the ways her co-workers speak about HIV+ people while being HIV+ herself. Also women, who date men and are afraid of being left because they are ill: this not an unlikely scenario. Hirsch looks into statistics (recognizing there is only data on hetero relationships), dives into the reasons and looks at queer relationships via interviews as well.

Hirsch’s writing is great and I would have read hundreds of pages more (but I am also happy this rather slim volume exists to put into the hands of everyone). One of the few things I found lacking was how Hirsch does not really go into how fatness is such a defining factor how one is treated at the doctor’s. This is strange for in general she is very good at pointing out how different women are affected differently. But all in all I could relate a lot, but also learned new things and gained insights.

Sonya Huber: Pain Woman Takes Your Keys. And Other Essays From a Nervous System (2017)

This book made me think, wonder, and laugh – but most of all I recognized myself and some of my experiences in this book in a way I had not before. In her essays Huber writes about her experiences with chronic illness and pain, looks at the (US) health system, analyzes common discourses on health/ illness and asks what pain actually is/ means/ does. The tone changes from poetical to outright snarky, the form from essay to open letters and lists. I loved this variety for it also stands in for the different approaches to and experiences of pain.

Huber looks at how the health system and health providers often fail chronic pain patients (i.e. by not taking women in pain serious, by focusing on the possibility of pain med addiction, by using pain scales which do not provide any insight), but she also writes about the difficulty to free oneself from certain ideas of productivity/ parenthood/ how life is supposed to be, sexuality or the lack thereof and social media representations of life with chronic pain/ illness.

Of course the book cannot discuss all these aspects in an exhaustive way in its 180 pages, but Huber maps out a huge field of what we could consider when discussing pain. The essay collection thus is a great starting point.

Samantha Irby: Wow, No Thank You. (2020)

Wow, no thank you. is Samatha Irby’s third essay collection. Irby moved from Chicago to live with her wife (and her two children) two a small rather Republican-leaning town in Michigan. In her essays, she writes about the ensuing changes in her life like trying to make new friends as an adult or dealing with house repairs. But she also dives into what it means to live with Crohn’s disease, body image, her favourite songs from the 1990s and her experience writing for the TV show Shrill.

I saw a lot of glowing reviews for that book and then thought, maybe, this is the right book to read at this moment when my mind feels mostly frazzled. And I did enjoy reading the essays. I laughed out loud several times. But while I was entertained for most parts, some of the essays in the middle dragged a little bit for me and often I wished for a bit more depth, a bit more analysis, a bit more conclusion or an epiphany. But I think that says way more about my specific reading taste than the quality of the book.

Shayda Kafai: Crip Kinship: The Disability Justice & Art Activism of Sins Invalid (2021)

Founded in 2005, Sins Invalid is a performance project rooted in disability justice and – as their website states – “incubates and celebrates artists with disabilities, centralizing artists of color and LGBTQ / gender-variant artists as communities who have been historically marginalized”.

In “Crip Kinship. The Disability Justice & Art Activism of Sins Invalid”, Shayda Kafai documents the history and praxis of Sins Invalid and analyses how the project tackles or relates to topics such as comunity, storytelling and artmaking, education, the titular crip kinship, sex and pleasure, beauty, and manifesting futures.

This approach makes this book so fruitful to read on many levels: you learn about the specifities of the project but also in more general about disability justice as a concept and praxis (“In 2005, disabled, queer of color activists Patty Berne, Mia Mingus, and Stacey Milbern conceived Disability Justice in community with Leroy F. Moore Jr. -the cofounder of Sins Invalid and the founder of Krip-Hop Nation-and disabled, trans activists Sebastian Margaret and Eli Clare. As a movement building framework, Disability Justice not only responds to the gaps in the mainstream Disability Rights Movement, but also offers principles framed in wholeness and persistence. […] Disability Justice begins to formulate strategies of survival for all our disabled, queer of color bodyminds.”)

This book is a hopeful book not by glossing over anything but by showcasing the potential joys of community, art, and trying to create a better, more inlusive future in the now. As Kafai writes:

We, the disabled, the chronically ill, and the Mad carry within us archives. We are intergenerational memory banks filled with the labor, organizing, and artmaking of our radical disabled, queer of color contemporaries, elders, and ancestors. We carry stories of resilience and survival, stories of growth and trauma. In sharing our crip stories, we unearth legacies of colonialism and nondisabled supremacy. We, dear reader, craft ourselves new routes to follow.

Alison Kafer: Feminist, Queer, Crip (2013)

Review upcoming.

Frida Kahlo: The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait (2005)

One of the most beautiful books I own is this annotated facsimile of Frida Kahlo’s diary.

Porochista Khakpour: Sick: A Memoir (2018)

Porochista Khakpour felt a little (or even a lot) off in her body for most of her life – there were aching, dizzy spells, and all kinds of diffuse symptoms. Her memoir “Sick” chronicles her life as being a sick person without a diagnosis because doctors diagnosed late stage Lyme disease only quite late. The book is not about a straightforward quest to health or at least an understanding. Instead, the book meanders, jumps back and forward. The chapters are roughly sorted with regards to locations as Khakpour constantly moves between Los Angeles and New York, but also Santa Fe, Leipzig (Germany), and other places, after first being displaced as a child fleeing with her family from Iran to the USA. She states: “I sometimes wonder if I would have been less sick if I had a home.” The structure makes sense since her trials to find a home, a place she feels comfortable in, is also linked to her alienation from her body. The nonlinear narrative is equally connected to some questions which might never be answered: When did she contract Lyme? And where?

Khakpour’s narrative is not one to easily grapple with. She writes about drug addiction (and the mix of recreational and party drugs and drugs she (first) took to fight some symptoms), difficult relationships, and a lot of uncertainty. She acknowledges blank spaces and the decisions to leave certain aspects out of the book. This is not “the whole story”, as no memoir ever is “the whole story”, but in contrast to many other books, she makes this very clear.

Khakpour also writes: “I’ve never been good at being sick. […] I am not a poster child for wellness.” This admission, which comes late in the book but is the sentiment throughout, makes this book so interesting: Khakpour did not try to appeal to an able-bodied audience who might prefer a simple story of suffering and finding truth (by a person who earned sympathy through good behaviour). She denies this impulse and instead goes for the complexities of life. I am very glad I read this book though at times I lost interest in the particularities – not due to the content or the general structure but to the writing style which did not always work for me.

Luisa L’Audace: Behindert und stolz. Warum meine Identität politisch ist und Ableismus uns alle etwas angeht (2022)

Review upcoming.

Shayla Lawson: How to Live Free in a Dangerous World: A Decolonial Memoir (2024)

Review upcoming.

Amanda Leduc: Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space (2020)

Whether we acknowledge it or not, the stories we tell ourselves as children shape the world that we encounter. Fairy tales and fables are never only stories: they are the scaffolding by which we understand crucial things. Fairness, hierarchy, patterns of behaviour; who deserves a happy ending and who doesn’t. What it means to deserve something in the first place; what happy endings mean in both the imagination and the world.

In “Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space”, Amanda Leduc interweaves memoir with cultural analysis looking at the ways disability and bodily difference is portrayed in fairytales – from the tradional tales to Disney adaptations – and how the impact of these narratives. Leduc writes about her own experiences with cerebral palsy, her own longings and dabbling into writing, and the complicated representations she encountered in books and films. At one point she comments:

We turn disability into a symbol because it has been socialized to be not useful – a burden on society, an uncomfortable ending. If disability is instead seen in story as a metaphor, there is potential for the happy ending as the able-bodied world knows it to truly be achieved. If a disability is not a disability so much as a symbol of something else, then once that symbol is realized, the disability can go away.

I found the book very engaging and underlined a lot. While it wasn’t the first time I have thought about disability represention in narratives in general and fairytales in particular, I really enjoyed following Leduc’s analysis and everything she shared from her own life (and how she connected these two strands). I will say though while she did attempt to not solely focus on disability as such but also connect with other categories of difference I wished for more of that (and more depth in that).

Give me stories where disability is synonymous with a different way of seeing the world and a recognition that the world can itself grow as a result of this viewpoint.

Andrew Leland: The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight (2023)

Due to retinitis pigmentosa, Leland moves from sightedness to blindness in his adulthood. In this wonderful book he documents this process, his reckonning with internalised ableism and his efforts to connect with blind culture. This makes this book very personal on the one hand but also a more general insight into blind experiences, community and culture in the US.

A truly smart, funny and incisive book.

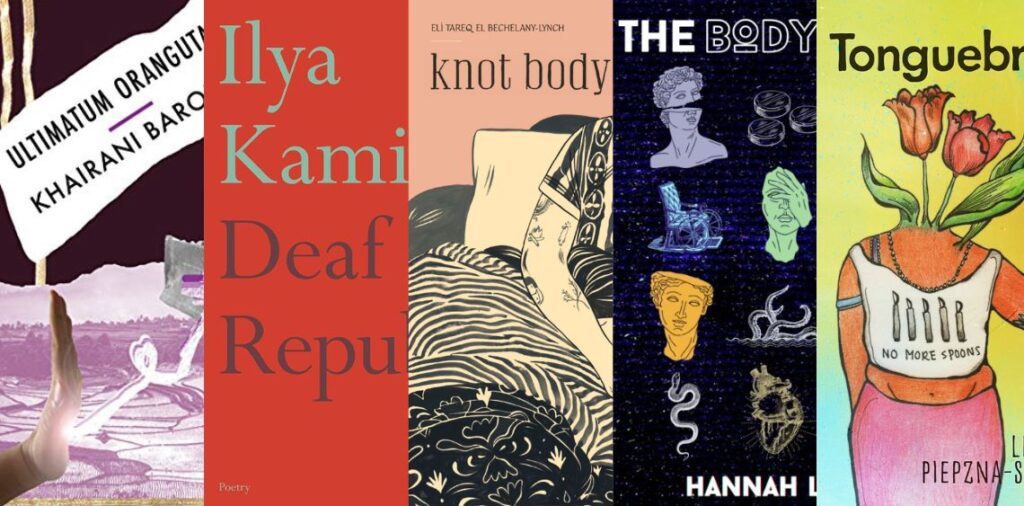

Audre Lorde: The Cancer Journals (1980)

Review ucpoming.

Fiona Lowenstein (ed.): The Long Covid Survival Guide: How to Take Care of Yourself and What Comes Next (2022)

This book is written by Long Covid patients for Long Covid patients – but as so often, everyone has something to gain by reading these texts touching topics such as getting diagnosed, cronfronting medical racism and coping with specific symptoms like fatigue. Some of the contributions are better written/ structured than others but that doesn’t change that this is a valuable collection and a good start to read about Long Covid.

Eliah Lüthi: beHindert & verRückt: Worte_ Gebärden_ Bilder finden (2020)

beHindert & verRückt, edited by Eliah Lüthi, was published this month. When it arrived I just wanted to leave through and put it away for later – but then I found myself reading it in its entirety. This anthology combines prose, poetry, comics, paintings – there are also audio pieces and videos in German sign language. Through fiction and non-fiction the anthology offers a wide array of thoughts, experiences, visions by disabled people. It’s a must-read.

Chella Man: Continuum (2021)

Review ucpoming.

Greg Marshall: Leg: The Story of a Limb and the Boy Who Grew from It (2023)

Greg Marshall grew up amidst three siblings with a dad with ASL and a mother, who was in and out of cancer treatment, bthough also always writing. Marshall himself had a limp and medical procedures in throughout his childhood but this was never really made a topic of discussion (the most he was told, was that he had had “tight tendons”). Only as an adult, he realizes that he has cerebral palsy – and he feels like he has to come out once again: now as disabled after already having come out as gay.

Leg: The Story of a Limb and the Boy Who Grew from It is really a wild memoir. Marshall’s childhood and family feel unique and he tells his story with a strong voice infused with humour. But the memoir also shows that you can not pretend away a disability and what we might lose by not being able to claim our disabilities (community, support, and mental aspects) – and what it means to be lied to by multiple people for all your life with regards to your own body.

It’s a book about finding yourself (again and again), about navigating a messy world (and a messy self), and about the complexities of family ties. I really enjoyed diving into this story and reading Marshall’s reflections, but the way he writes about his sister who is possibly autistic felt still coloured by unexamined ableism which was disappointing.

Tessa Miller: What Doesn’t Kill You. A Life with Chronic Illness – Lessons from a Body in Revolt (2021)

See, chronically ill people grieve two versions of ourselves: the people we were before we got sick and the future, healthy versions that don’t exist (or, at least, look much different from what we’d imagined). There’s no guidebook for this kind of ongoing self-loss. No Hallmark card that says, “Sorry you’ll never be yourself again.”

The writing is very approachable and Miller’s alternating structure between describing her own (pretty harrowing) experiences, laying out statistics and interviews as a more journalistic approach, and offering concrete advice in more self-help-y parts of the chapters, certainly keeps you glued to the book. But alas, I do not breathe through this book. And this might be a compliment.

Miller looks at different topics in her chapters. The one which affected me most so far was the one on grief. There is just a lot to grieve and it is somewhat ongoing, especially if you have illnesses which are progressive (also as most chronically ill people know: if you have one, the chances are high you will collect more diagnoses over time). Next to a lot of other very helpful tips on how to deal with this grief and how to reframe and reconsider some very persistent thoughts you might have, Miller writes at one point: “You can feel sad and create a meaningful, joyful life.” I can’t tell you yet how much this sentence will impact the rest of my year and probably life, but I leave it here for anyone else who might need to hear this.

Mika Murstein: I’m A Queer Feminist Cyborg, That’s Okay (2018)

A really fantastic book (with one of the best titles) in German which brings together Murstein’s own experiences but also always looks at the wider community. For example, Mika Murstein uses an interview to speak to different experiences especially at the intersection of race, gender, and ability. Furthermore the book offers insights into theory and history of anti-ableism and for example the role of online communities.

Walela Nehanda: Bless the Blood: A Cancer Memoir (2024)

Very impressive memoir in verse about life with leukaemia as a young fat Black queer non-binary person. Nehanda dives into complicated family dynamics, medical racism, suicidal ideation, the way fatness and disability and Blackness complicates getting medical treatments, navigating a rocky romantic relationship through it all. I can also recommend the audio version which is really well made with some subtle sound effects interwoven with the narrative.

The book is labelled as YA and I am not sure why. Nehanda is in their twenties and writes about their lives in the twenties. I also don’t think the style necessarily puts it in YA. Which isn’t to say that I don’t believe it could be a powerful read for a YA audience. But well it just shows how Add a comthernabel YA is more a marketing tool than anything else.

Nanjala Nyabola: Strange and Difficult Times: Notes on a Global Pandemic (2022)

You hope that one of the things that people have learnt through this experience of the pandemic is that capitalism can make any one of us disposable at any time, depending on the exigencies of the moment. You hope that people notice and condemn the argument that keeping the machine going was a more important outcome than providing care for the most vulnerable. But based on the way policymaking continues to steamroll over the concerns of people who don’t fit capitalism’s description of productivity, it seems we haven’t fully appreciated the lesson. Of course, empathy demands that we provide for each other in our communities, not just because one day we might need it, but because it’s the right thing to do. But even in that context, the lack of solidarity with these groups has been shocking and a terrifying window into the paradigms of disposability that have taken root worldwide.

If you only read one book on the pandemic, make it this one. The essays in “Strange and Difficult Times” are incredibly nuanced and tackle the topic from many different angles and through different writing approaches. Nanjala Nyabola writes about the topic of mask wearing from a Kenyan perspective (and I found the detailed account of the ways masks wear adopted absolutely fascinating), the strange discourse in Western media about why African countries had documented less deaths of Corona than said media would have predicted and the global politics of producing and distributing vaccines. She also dives into historical context and dissects what can be found in colonial archives about the flue pandemic in 1918 where she states: “The official story of how Africans behaved during the pandemic lacks empathy and nuance because those in power did not see Africans with empathy and nuance.” A still often true sentiment.

So in the end this is not only a (fantastic) book about the Corona pandemic but also in general a great book which makes us question the ways we talk about diseases and people’s reactions to these as well as the long reach of colonial legacies.

Bex Orlington (ed.): Sensory: Life on the Spectrum (2021)

First of all: I love that cover. I also liked that this anthology really includes a lot of artists with all their perspectives and their different art styles. But in general, it’s one of these books I am very happy it exists but I didn’t love it. The comics were art-wise hit and miss and as they each are only a few pages long it felt a bit surface level (and repetitive). I am not sure who would be the perfect reader? Potentially people who just start thinking about autism? (Though I can also imagine that some people will find just the moments of recognition enough to fully love this book!)

Meghan O’Rourke: The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness (2022)

Review ucpoming.

Lucia Osborne-Crowly: My Body Keeps Your Secrets (2021)

Review ucpoming.

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna‑Samarasinha: Care Work ‑ Dreaming Disability Justice (2018)

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha writes about the history of disability justice (and fear of this movement being co-opted), rethinking care and access, suicidal ideation, new models of survivorhood, ‘call-out culture’, and making space for disabled/ chronical ill elders. Centering the experiences and knowledge of disabled/ sick/ Mad QTPoC, especially femmes, Piepzna-Samarasinha documents activist history (which gets often forgotten or over-written), offers practical tipps (like her “Chronically Ill Touring Artist Pro Tipps”), discusses conceptual work (for example on ‘care webs’), and shows attempts to make things works. There are essays, lists, and conversations with other artists and activists in this book and it all adds up to a memorable read; an emotional read.

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha: The Future Is Disabled: Prophecies, Love Notes and Mourning Songs (2022)

Review upcoming.

Devon Price: Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity (2022)

Review upcoming.

Brontez Purnell: Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt: A Memoir in Verse (2024)

A very special small book. Bridges I’ve Burnt is a memoir of sorts. Purnell shares in 38 short pieces of prose poetry so many of his experiences and reflections as a gay Black man. Among other things, he discusses growing up in the South, his experiences writing for TV, about a literary conference, watching the Bay area gentrify – and also about ADHD.

Syan Rose: Our Work Is Everywhere: An llustrated Oral History of Queer and Trans Resistance (2021)

It’s part graphic nonfiction, part thank-you note, part gay theory paper, part activist gossup column, & the rest is a surrealist drean in which we know why we we’re here & what we need to do.

Our Work Is Everywhere: An Illustrated Oral History of Queer and Trans Resistance by Syan Rose is such a beautiful, calming, informative and energizing book. Rose interviews and portrays a wide range of activists and their work. I love learning about all the different small (and not so small) ways people use to create these pockets of community, change, survival, resistance. And the illustrations are absolutely stunning. The only thing I will say is that the font is at times very hard to read.

H.C. Rosenblatt: aufgeschrieben (2019)

aufgeschrieben by H.C. Rosenblatt is a very special German-language book, and a hard one to read. It’s about immense violence and its repercussions, about loyalty and parental figures, about disableing systems, dissociation and survival. Rosenblatt is a survivor of violence living with DIS. The text is episodic, closely observing and interweaves detailed descriptions of the physical (?) space the narrator(s) is/are in, personal reflections and questions and wider societal analysis. Some thoughts are easy to follow, other associations might remain impenetrable as violence renders some realities incomprehensible.

Sarah Ruhl: Smile: The Story of a Face (2021)

Review ucpoming.

UPDATED: Marian Schembari: A Little Less Broken: How an Autism Diagnosis Finally Made Me Whole (2024)

What I really liked about this memoir is that Schembari doesn’t shy away from writing in-depth about all the aspects which aren’t “pretty” and “quirky” like meltdowns as an adult (in her case especially also as a parent). I also think the way she describes her way to a later in life diagnosis will be relatable to many (except for how quickly she got someone to diagnose her once she decided she wanted an official diagnosis).

Sarah Schulman: Let The Record Show – A Political History of Act Up New York, 1987-1993 (2021)

Let The Record Show is based on 188 long-form interviews conducted with surviving members of ACT UP New York between 2001 and 2018 and Schulman’s own experiences within ACT UP and the AIDS movement. This book positions itself against some other (dominant) narratives about AIDS activism from recent years which often focussed on only very few people (white men mostly). Schulman argues that ACT UP was more decentralized than this discourse allows and that this organizational form (and the many different people contributing at different times and in different ways) made ACT UP (often) successful.

Schulman is not only interested in retelling some history but actually drawing lessons for today’s organizing. She writes critically and compassionately, drawing out the complexities of organizing and just lived messy lives. I have read roughly 130 pages so far (it’s almost 800 pages long) and it’s incredible. Every few pages I feel I learn something new, being challenged in my perception or take something away on how to view activism today.

Jenn Shapland: Thin Skin: Essays (2023)

“This is a book about the joys and perils of our dissolving boundaries: the physical boundary of our skin as it absorbs chemicals, the emotional border where real fear meets cultivated violence, the obscured line from our desires to our material things, and the imaginative realm beyond our presribed expectations for a full life and toward expanded ideas of personhood, meaning, and purpose.” – Jenn Shapland

Thin Skin, the essay collection by Jenn Shaplan, is such a wonderous book full of delightful connections, intricate questions, deep personal reflections and a lot of research. I will say, there was at least one essay which didn’t work for me personally and I have some concrete criticism of others. But still there were so many parts I deeply, deeply loved.

The titular Thin Skin, for example, is about so much: finding home, nuclear test sites, about landscapes and its people, toxic material (and which communities are most affected), Marie Curie, bodies and illness, the queer history of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. The text is built on interviews with people such as Marian Naranjo (founder of Honour Our Pueblo Existence) and Cheryl Johnson (director of People for Community Recovery in Chicago. The text is deeply touching but also leaves you with a lot to think about.

The other essay, which made me underline so many paragraphs, was The Meaning of Life which reflects on what it means to not want to have children (as a queer, white woman). This text is so vulnerable and at times angry (I have barely ever seen some of the more uncharitable thoughts which might have crossed my mind reflected in text), but it is also nuanced and layered, connecting the personal with bigger societal questions and histories. (My only caveat with this essay: I always find it questionabe when people lean into certain ideas about witch hunts in Europe without drawing the connection to antisemitism because that way something crucial is missing and I feel the whole base of some arguments become less stable.)

Overall, I will return to this book. I am sure of that.

UPDATED: Ashley Shew: Against Technoableism: Rethinking Who Needs Improvement (2023)

This is a really good starting point to think about technology and disability, dismantling actual barriers and ableist ideas of “fixing”. Shaw not only has worked on these topics in theory as a bioethicist but brings her lived experiences as a “hard-of-hearing chemobrained amputee with Crohn’s disease and tinnitus”. It is quite short and I would love to read something even longer on these topics.

Maxfield Sparrow: Spectrums: Autistic Transgender People in Their Own Words (2020)

Review upcoming.

Lou Sullivan: We Both Laughed In Pleasure: The Selected Diaries of Lou Sullivan: 1961-1991 (2019)

Lou Sullivan was born in 1951 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and grew up to become an influential trans activist who – among other things – fought for the recognition and thus access to rescources for gay trans men.

Covering 30 years of Sullivans life (which was cut short by AIDS), it is an astounding document. This continous effort allows the reader to really follow Lou’s thoughts as a child, witness the ways his desires and the way he relates to gender, gender identity and gender performances shift over time, and see Sullivan as one person in a bigger network of queer and trans people. The diaries also document that his path – as is the path for many trans and queer people – is not a straighforward succession of some steps leading to a clear goal, but there are many loops and back and forth between doubts and euphoria. At times this can be incredibly frustrating to read – the way real life rumminations and “bad” choices are frustrating. But the diaries are also fun, erotic, emotional.

There is a lot to love about this diaries, even if you don’t always agree with Sullivan. I loved how the diaries documented Sullivan’s desire, communities, activism and the media discourse around trans people. It is also wonderful to see how his Catholic family rallies around him.

About his HIV/AIDS diagnosis Sullivan said: “I took a certain pleasure in informing the gender clinic that even though their program told me I could not live as a Gay man, it looks like I’m going to die like one.” In his diaries, he writes repeatedly that he wants his diaries to be published. It is, of course, sad that he did not get to see this goal accomplished but I am glad, that we, as readers today, have now access to his thoughts and experiences and get such a great glimspse into a specific time and place.

Meredith Talusan: Fairest: A Memoir (2020)

Review updated.

Clara Törnvall (transl. by Alice E. Olsson): The Autists: Women on the Spectrum (2021/ 2023)

Review upcoming.

Kaleigh Trace: Hot, Wet, and Shaking (2014/ 2020)

I read the German translation of Kaleigh Trace’s Hot, Wet, and Shaking. in which Trace writes about sex, bodies, and difference from her perspective as a feminist queer disabled woman. On a content level there was so much interesting stuff -Trace writes about everything from her first experiences to her abortion, from working in a sex shop to experiences with ableist street harassment. I just never really got into the writing style (though she explains very poignantly why she writes the way she does).

Hannah Wahl: Radikale Inklusion: Ein Plädoyer für Gerechtigkeit (2023)

Radikale Inklusion geht davon aus, dass wir genau so viel Inklusion leisten müssen, dass allen Menschen gleiche Chancen zuteil werden und sie ein selbstbestimmtes, erfüllendes Leben führen können […]. Das heißt, das Patriarchat bekämpfen, wie auch die ökonomische Ausbeutung, Altersdiskriminierung und den Erhalt von Parallelwelten. Radikale Inklusion eröffnet den Raum für einen Diskurs, der explizit politisch sein will und intersektionale Perspektiven miteinbezieht. Das heißt nicht nur, eine abstrakte Utopie von einem Paradies auf Erden zu schaffen, sondern auch zu besprechen, wie wir systemimmanente Verbesserung erwirken können, ohne das Ziel aus den Augen zu verlieren.

Mit “Radikale Inklusion: Ein Plädoyer für Gerechtigkeit” hat Hannah Wahl ein Buch verfasst, welches auf weniger als 130 Seiten (inklusive einer Zusammenfassung in Leichter Sprache, die es auch frei zum Download gibt) eine präzise Übersicht gibt über die aktuellen Lebensrealitäten behinderter Menschen in Österreich und Deutschland – und warum nur radikale Inklusion und nicht irgendeine Inklusion Light Variante das Ziel sein kann. Wahl schaut auf die Bildungssysteme, Heime und der Umgang mit Gewalt gegen behinderte Menschen. Dabei macht sie auch deutlich, dass es keine lineare Entwicklung gibt, sondern häufig einen Schritt nach vorn und zwei zurück geht. Dabei fokussiert sie auf die zwar unterzeichnete aber nie wirklich umgesetzte UN-Konvention über die Rechte von Menschen mit Behinderungen und legt den Finger genau da hin, wo es wehtut, wenn sie – mit all ihrer Expertise als Teil des Unabhängigen Monitoringausschusses zur Umsetzung der UN-Konvention – anklagt: “diese vorgetäuschte Orientierungslosigkeit [hinsichtlich der benötigten Aktionen] ist nicht mehr als eine Strategie im Sinne der Umdeutung von Inklusion”. Sie schreibt: “Die Umdeutung von Inklusion ist ein Sabotageakt.”

Natürlich sind die Un-Konventionen nicht der einzige Referenzrahmen für radikale Inklusion und das hätte durchaus auch in diesem Buch noch etwas mehr Erwähnung finden können. Genauso wünschte ich mir ein paar mehr zitierte Schwarze, PoC und migratisierte behinderte Menschen aus Deutschland und Österreich. Trotzdem aber ist es ein Buch, was ich so ziemlich allen in die Hand drücke möchte, von Politiker*innen, Ärzt*innen und Lehrer*innen bis hin zu Freund*innen und Nachbar*innen. Denn hier gibt es konkrete Beispiele und Argumente – und ein überzeugendes, kämpferisches Plädoyer für grundlegenden gesellschaftlichen Wandel.

Nick Walker: Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities (2021)

Review upcoming.

Esmé Weijun Wang: The Collected Schizophrenias: Essays (2019)

Review upcoming.

Lucy Webster: The View From Down Here: Life as a Young Disabled Woman (2023)

Loved the parts in which Lucy Webster really focuses on her own experiences. There is a lot in there for example about living with personal assistance or about family planning as a disabled (cis) woman. It does fall a bit short when she makes broader points as these remain very much limited to her perspective but get then generalized (as when she speaks a lot about intersectionality but race never being considered and also how she constructs womanhood in solely cis and straight). But still a worthwhile read.

Alice Wong (ed.): Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories From The Twenty-First Century (2020)

Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong, was published at the end of June and brings together essays which have been published before and those specifically written for the anthology. I am only a few essays in but already feel confident recommending this one wholeheartly. At the end of the book is also a great rescources list with more books (non-fiction, fiction, poetry, websites etc.) This makes this anthology a particular great starting point for people who want to engage more with disability (rights) perspectives.

Alice Wong: Year of the Tiger (2022)

Review ucpoming.

Alice Wong (ed.): Disability Intimacy: Essays on Love, Care, and Desire (2024)

I liked that this anthology again brought together a variety of perspectives but as with the previous one I had to realize that I prefer another kind of essays. While there are some standouts, I often wished for deeper analysis in the texts and a bigger variance in tone and approach.

Fiction

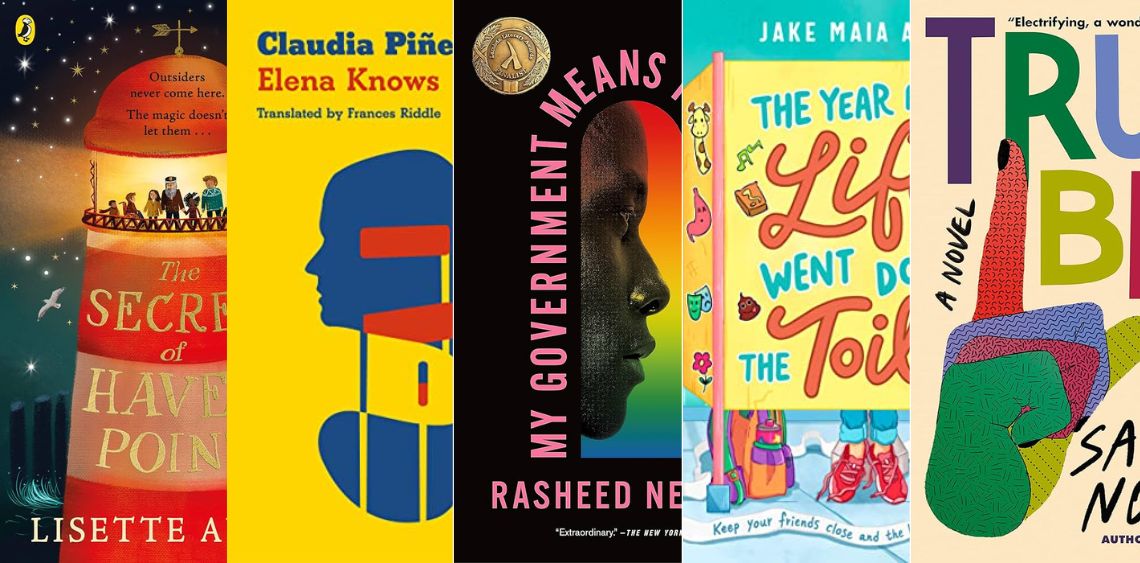

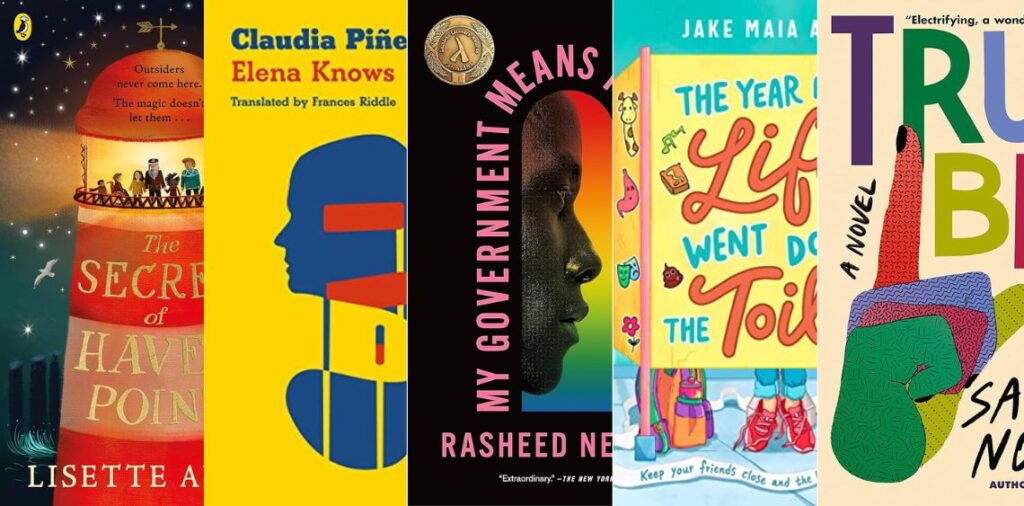

Jake Maia Arlow: The Year My Life Went Down the Toilet (2023)

Twelve-year-old Al Schneider is just diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease. But that’s not the only recent shift in her life: She is also pretty sure that she likes girls and questions what this means for her. This is an incredibly sweet MG novel which shows the importance of finding community. It is also equally a very vivid depiction of living with Crohn (from pain to bathroom incidents) and a slightly fantastical one (the great medical support).

Emily Austin: Interesting Facts About Space (2024)

This novel follows Enid who is obsessed with space (and can tell you all about her favourite space facts), loves to listen to true crime podcasts, is moving from dating one woman to the next, and has some kind of phobia of bald men. As she tries to rekindle the relationship with her estranged half-sisters and starts a seriours romantic relationship, she starts to feel like someone follows her and everything seems like it might fall apart.

The way Austin intertwined the experiences of physical disability (partial deafness), neurodivergence (autism) and CPTSD – I thought this was really good. This novel is funny and heartbreaking and ultimately even hopeful.

Emily Austin is not deaf in one ear like her protagonist but blind in one eye. She wrote about some of her experiences which influenced the novel in an article for The Nerd Daily.

Lisette Auton: The Secret of Haven Point (2022)

When Alpha was a baby she was left in a soap box and taken in by Cap’n who lives in a lighthouse (and in whose beard always lives a kitten) and Ephyra, a mermaid who lives with her clan in the sea just off the coast. Over the following years more and more people arrive at this special place whose magic boundaries only allows disabled people of all ages to step in and find a place of community, safety and belonging. The inhabitants call themselves the Wrecklings as from time to time – in cooperation with the mermaids – they raid ships to stock up on necessary supplies like medication. But this seemingly utopia starts to crumble at the beginning of the novel when mermaids disappear and Alpha gets the distinct feeling of being watched.

The Secret of Haven Point is a Middle Grade novel which puts disabled people front and center. This is very much a book about disability as the protagonists’ disabilities are always part of them and I really appreciated how Auton, who is disabled herself, describes the different ways people do things. (For example, about one character she writes: “So she has to make choices, sometimes between big things like a party, or watching a film, and sometimes between brushing her teeth and sitting up. She says she’s a life in balance. She pulls her weight as much as anyone else, but on her own terms like we all do; we measure worth differently here.”) And beyond the characters specific experiences the novel starts an overall discussion on what disabled people might need to live full and free lives. All this is packed in a really good and suspenseful adventure and mystery story.

I loved the world this book builds and the glimpses of an inclusive space it gives the reader, the attention to detail for different accomodations. But this novel also does not sugarcoat living with disabilities in a ableist world as it makes clear why this secluded place was needed in the first place and the pain which goes hand in hand with the need of such a place.

Keah Brown: The Secret Summer Promise (2023)

Andrea is looking forward to this summer. After she had to spend the last summer mostly in recovery from surgery for her cerebral palsy, she now has all the plans. Together with her best friend, Hailee, she put together a summer to do list to make sure this will be the best summer ever. But Andrea also added her own secret point: Finally ending her crush on Hailee and may be falling in love with someone else.

Keah Brown – who is also known as the person starting the hashtag #DisabledAndCute and author of The Pretty One: On Life, Pop Culture, Disability, and Other Reasons to Fall in Love With Me – has written a fun summer-y YA novel about first love and friendship.

I will say a lot of conflict is based on not characters not communicating well with eachother, something I don’t particular enjoy to read, but here I didn’t really mind as it did fit quite well with these slightly messy teenagers who are still to figure out a lot.

I loved the way Andrea’s disability was always present but not always the plot point. This is a book about a Black disabled queer girl who falls in love, is desired, makes mistakes, loses and wins back friends. A book about summer joys like skinny dipping and ice cream but also all the drama.

I was sometimes slightly disorientied timewise (sometimes I thought weeks must have passed but than apparently it wasn’t longer than a week?) but in the end it did not take away from my enjoyment and it was the perfect beach side read.

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: Starling Days (2019)

Starling Days follows Mina, a Chinese-American classisist, and Oscar, who is the illegemate child of a Japanese-American business men and a British woman. The two have been together for more than 10 years, when one day Mina is picked up by the police suspecting her to try to jump from a bridge. This episodes leads Oscar to proposing to leave New York for some time and go to London. A change of scenery. In London Mina meets Phoebe – and starts to fall for her.

This novel portrays what it might look like to live with depression and suicidal ideation (aswell as polycystic ovaries). It dissects the everyday and the complexities of love, support, desire and the limits of each. Starling Days also speaks about belonging and family. Buchanan shows Oscar juggeling his fear of losing his wife, the frustration of not knowing how to make things better effectively and the added stress of his complicated relationship with his father. Mina is a classisist and works on a side project on those women who survive in Greek and Roman myths. And the question she asks of these texts reflects the question of her life: What does it mean to survive? How long do you have to survive in order for it to count?

The portrayal of Mina and her relationship dynamic felt incredibly true to me, especially the knowing one does hurtful stuff but not being able to get out of ones mind. Starling Days is a beautiful, honest novel. Though sometimes tragic it is also at times very funny.

At a reading I attended Buchanan said that she had in the beginning planned to also flesh out Phoebe’s perspective. I do see why it made sense to cut that out but still at times I’d ached for more of her take on what is happening.

Lynn Buckle: What Willow Says (2021)

She would describe the gravel path with a flat-handed shaky sign, palm down, making a circular motion then fingers dropping bits, sometimes ending in a flick. Moving on from the forest entrance, the ground feels compacted, earthy, reassuringly well-trodden. Both hands brought together in a slow flat horizontal clap, with an extra nod for good measure. That.sign could already mean something else. In context, we will know it is ours.

What Willow Says has won the Barbellion Prize earlier this year and I absolutely see why. This is an incredibly beautiful book about a grandmother and granddaughter: A brilliant meditation on language and communication, interwoven with stunning nature writing and writing on ailing bodies.

I loved how this book is full of myth and metaphors but also portrays the very real experiences of Deaf and hard-of-hearing people (especially wonderful to read this specific multi-layered approach as so often we read writing of bodily difference either solely as metaphor without consideration of disabled people – or as an lazy signifier for bad people). There is a deep melancholy in this book but also subtle humour and I really appreciated that tone.

Jen Campbell: The Beginning of the World in the Middle of the Night (2018)

Review updated.

Becky Chambers: To Be Taught If Fortunate (2019)

Elena likes visual checks. She likes tangibility. The wind and sky were ephemeral enough, she told me once. If she’s going to study them, she wants to feel them.

At this point, Becky Chambers is well known for her particular brand of sci-fi: quite, soft, queer, and more interested in daily life than most. And while this new novella is not set in the Wayfarer universe and has its distinct story to tell, it shares a general vibe with Chambers’ series.

To Be Taught, If Fortunate is set in the 22. century. Humanity has developed modes of somaforming which enables humans to adapt more easily to other planets (as an alternative to terraforming planets to adapt to humans). Ariadne, an engineer, is part of a space expedition – together with three scientists. The novella is one message to Earth in which Ariadne chronicles their experiences on four planets and pleads their case – because while they have been in space for decades, something has happened on Earth

To some, this might be a slow, pretty nerdy book. I loved it for these reasons. While Ariadne describes the crews ‘adventures’, she not only transports the joys of acquireing knowledge but also discusses the ethics and limitations of doing so. Chambers managed to write a sci-fi novel about ‘discovery’ which actually meaningful interrogates a colonial mindset. For a book only 130 pages long, there is much to think about. (Bonus: basically all LGBT+ cast and shows a possible language for writing about health and bodily differences without reinstating oppressive norms.)

Alina Chau: Marshmallow & Jordan (2021)

A pretty cute graphic novel set in Indonesia following a disabled girl who “finds” a white elephant. It’s about friendships and community – and about sports. It also touches upon the climate crisis and how Indonesia is impacted. (Note though: the author does not share the protagonist’s disability or use of a wheelchair/ mobility aids.)

Alison Cochrun: Here We Go Again (2024)

This romance novel follows two (neurodivergent) women in their early thirties who once were friends but had a fallout years ago. They have to reunite to take their dying former English teacher on one last roadtrip. I did love the intergenerational queer relationships in this novel (though there was also a bit of the young white queers (who are of course the leads) being inspired by the older queer BPoCs). There were also some interesting discussions on death and grief. I was touched by some of the scenes. But I have to admit both protagonists felt rather like they are in their very early twenties and this irritated me throughout.

Akwaeke Emezi: Pet (2019)

“You can’t sweet-talk a monster into anything else, when all it does want is monsterness. Good and innocent, they not the same thing; they don’t wear the same face.” Pet is Akwaeke Emezi’s second published book and first array into writing for a younger audience. In this novel, we meet Jam, a Black trans teenage girl, her parents Bitter and Aloe, and her best friend Redemption. They live in a town called Lucille which believes it has gotten rid of its monsters. Prisons are abolished. Guns are banned. Monuments of slave owners replaced with monuments for the victims of the former oppressive system (including those died in bomb raids in other nations (“nations are not even real”) and those who died because of cuts in the health care system). But what happens if one day one of Bitter’s paintings opens a portal and a creature enters Jam’s house with the goal to hunt a monster. Are there still monsters? Is Jam brave enough to find out? How do monsters look like? And who will believe her?

Pet is a beautifully written novel, clever, and heartwarming. It asks difficult questions about the dichotomy of good and bad, the possibilities of utopias, the complexities of revolutions, the consequences of forgetting ‘monsters’ – and the different faces of ‘evil’. I highly recommend this book for teen and adult readers alike.

Lastly, I want to share this quote of Emezi from their New York Times interview which perfectly captures the spirit of this novel: “So I was like, if I’m writing something for black trans kids, what spell do I want to cast? I want to cast a spell where a black trans girl is never hurt. Her parents are completely supportive. Her community is completely supportive. She’s not in danger. She gets to have adventures with her best friend. And I hope that that’s a useful spell for young people. I hope that’s a spell where someone reads that and they’re like, this is like what my life should be like. This is a possibility.”

Akwaeke Emezi: Bitter (2022)

Review upcoming.

UPDATED: Sarah Gailey: Eat the Rich (2024)

Some horror in comic form! A young woman visits for the first time the summer house of her rich boyfriend’s family and the horror quickly unfolds. Yes, this is a cannibalism story. But above all it’s a story about class and capitalism and about access to healthcare. It is very gritty. It is queer. And ultimately a revenge story.

UPDATED: Deanna Grey: Outdrawn (2023)

I really enjoyed this romance novel about two Black, queer rival comic artists who have to work together on a comic and fall for each other. It’s about family relationships, art making and finding one’s own way – and dealing with chronic pain. I loved how these two were so supportive of each other’s art and careers (even if it wasn’t always easy aiming for similiar things).

Claire Forrest: Where You See Yourself (2023)

Review upcoming.

Carlos Hernandez: Sal and Gabi Break the Universe (2019)

This is such a wild time traveling (and time breaking?) MG novel which is difficult to sum up but it is fun and full of heart. And one of the main characters has diabetes which is part of the plot but not the center of the plot.

Anita Kelly: How You Get The Girl (2024)

A lesbian, queer romance novel with one of the leads living with strong migraines. The novel follows Julie, who coaches a high school basketball team, who falls for Elle, foster parent to one of teens in the team and a former University of Tennessee basketball star.

Anita Kelly’s Something Wild & Wonderful remains my favourite in this queer romance series. I liked How to Get the Girl fine but didn’t love it. Just some tropes which are not my favourite. But I liked that we got some glimpses of the protagonists from the first two books and what they were up to.

J. Vanessa Lyon: Lush Lives (2023)

Lush Lives is first and foremost a romance between Glory Hopkins, who inhertied her Aunt Lucille’s Harlem brownstone, and Parkie de Groot, an auction house appraiser. It is also a novel about art and literature, morality, and the ways (especially Black) queer lives have been visible and made invisible. Parkie’s disability is rarely the main topic but it is consistently part of her experience of the world. This novel has very mixed reviews and while I didn’t love every aspect, I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Elvin James Mensah: Small Joys (2023)

Harley is a young Black man who – struggeling with anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation – and he just dropped out of university. He is caught up in a sexual affair with a man who gets of off degrading him (but not in a consensual way, rather in a white supremacist with internalized homophobia way) and his relationship to his father is fraught as his father still hopes to pray the gay away. In short: Life for Harley sucks. But moving back in with his best friend, he meets Muddy – another flatmate. Muddy is full of joy, a rugby player who is also an avid birder.

Small Joys by Elvin James Mensah is a quiet book – sometimes very funny, sometimes deeply sad – about friendship, desire (and the lack thereof), mental health and finding reasons to stay. This novel shows what happens once you might try to not find validation in the wrong places (or from the wrong people). It’s about the “small joys” we can find and how they might make up a worthwhile life.

I just loved Small Joys. I adore how this novel puts friendship front and center. And all the small moments portrayed. It’s earnest in this heartfilling and -opening way.

UPDATED: Carley Moore: Panpocalypse (2020)

Review upcoming.

Rasheed Newsom: My Governement Means To Kill Me (2022)

This really is one of my favourite novels I read in 2022. An incredible novel about a young Black gay man, Trey, who tries to figure out his life in 1980s New York. I loved the focus on activism (from housing rights to ACT UP) and community (like the one Trey finds in a bath house). I am always looking for fictional narratives which portray characters engaged in some kind of actvism but it’s a surprisingly little touched upon subject. So naturally I gravitated to My Government Means To Kill Me and it did not disappoint.

Sara Nović: True Biz (2022)

Charlie is a deaf teenage girl who transfers to River Valley for the Deaf and for the first time in her life is surrounded by other deaf people and especially people communication in sign language. Austin is another student at River Valley. In contrast to Charlie he grew up in a majority deaf family – but when his little sister is born and announced as hearing his world starts to fall apart. And then there is February who is hearing but the child of deaf parents. She is the headmistress of River Valley and fights to keep the school going – while also balancing her delicate homelife as the relationship with her wife shows cracks and life with her mother struggling with dementia is an ongoing challenge.

In True Biz, Sara Nović switches between these three perspectives to draw a lively portrait of life at this fictional school and ask important questions around language acquistion, the role of ASL, Deaf culture, and “integration”. The novel not only manages to create a group of interesting characters whose story lines I enjoyed following but also to depict the rich history ASL has and wealth that ASL is.

Some parts of the novel though felt a bit too didactic (and I do not mean the inserted ASL language and history lessons – a stylistic choice which worked perfectly for me). Especially, the insertion of a discussion on Black ASL felt a bit like an afterthought, even though the topic in itself and the realisation that a space which feels safe for some also often excludes others in some way(here Black Deaf students).

In their author’s note, Nović adds a list of closed schools for Deaf students accross USA and writes: “Today’s prevailing educational philosophy centers on a mainstream approach, but at what cost? For many deaf and hard-of-hearing students, the result has been a veneer of “inclusion,” without true equity.”

Ryan O’Connell: Just by Looking at Him (2022)

Review upcoming.

Nnedi Okorafor: Akata Witch (2011)

The first novel in Okorafor’s MG The Nsibidi Scripts series. The novel follows twelve-year old Sunny who was born in New York, U.S., but is now living in Aba, Nigeria. Sunny has albinism and while she would love to spend all day outside playing football, she often just can’t. But then she befriends Orlu and Chichi and a truly magical and suspenseful story unfolds. I really loved this when I read it first in 2011.

Kay O’Neill: The Tea Dragon Society (Tea Dragon, #1) (2017)

Review upcoming.

Diriye Osman: The Butterfly Jungle (2022)

Review upcoming.

Shelley Parker-Chan: She Who Became the Sun (2021)

Review upcoming

Claudia Piñeiro (transl. by Frances Riddle): Elena Knows (2001/ 2021)

Review upcoming.

Sonora Reyes: The Luis Ortega Survival Club (2023)

Review upcoming.

Cat Sebastian: The Queer Principles of Kit Webb (2021)

Review upcoming.

Tess Sharpe: Far From You (2014)

This is a YA thriller about Sophie who tries to solve the murder of her best friend (and other things…) Mina – though everyone believes it was a drug deal (set up by Sophie) gone wrong. But at the time of the murder Sophie had been drug-free for nine months already. Which barely anyone believes. This novel has a disabled, bisexual, recovering addict as its protagonist and it is a real page-turner. The writing wasn’t my favourite and some of the plot points were a bit over-the-top but can’t lie, during a time where I could rarely concentrate, I read this book in two or three sessions only.

Brianna R. Shrum, Sara Waxelbaum: Margo Zimmerman Gets the Girl (2023)

Review upcoming.

Rivers Solomon: An Unkindness of Ghosts (2017)

The HSS Matilda is a huge spaceship with clear hierarchies between the decks, the lower deck inhabitants being controlled, harrassed and forced to (uncompensated) labour. On this ship, which has left Earth over 300 years ago and is still supposed to be on the way to a Promised Land, racism and other forms of discrimination and violence are deeply engrained into its social and political system. Aster is a lowdeck worker and healer, assistant to upper deck doctor Theo, who is only called the Surgeon. When the current sovereign falls ill to a mysterious illness Aster – with the help of her deeply traumatized but resilent cabin mate Giselle – starts to make sense of the diaries of her late mother, beginning to unravel some of the secrets of the ship. At the same time – after the sovereign passed – the climate at the ship gets even more brutal than before.

This book is utterly beautiful and heartbreaking. Rivers Solomon manages to built a complex world, to inhabite it with a diverse cast of characters, and weave a breathtaking tale. They write gender diversity (and diverse representation of longing), diasabled and chronically ill people, and different dispostions in all kinds of ways in such a great and intelligent way. There is Aster who struggles to decode the non-literal meaning of what people say to her, who loves her things in order, but has to navigate a highly unorderly time. Theo grew up on the upper deck, the illigemate child of a upper deck man (an earlier sovereign) and a lower deck woman, struggling all his life with the imposed masculinity ideals. Giselle has lived through so much trauma, trying to find at least a few coping mechanisms. Mabel, who raised Aster after her mother died shortly after her birth, cares deeply about the women around her but abhores being seen as the motherly type. And these are just a few to mention.

There would be so much to say about this book, so much to disect, but let me leave it at this: I’d have wished for a different ending, because I loved these characters so much. That said the ending was perfect.

UPDATED: Rivers Solomon: Model Home (2024)

Ezri and their sisters, Eve and Emanuelle, have grown up in a gated enclave outside Dallas, where they were the only Black family around. But even though living in their house and this neighbourhoodn more often than not felt horrondous to the family, the parents decided to hang onto the place to prove that they could strive there. Consequently, Ezri hasn’t been to see their parents for a long time. When they return due to some mysterious messages, they find their parents dead. Has the house killed them? Ezri and their sisters are forced to reconsider their lives and what they believe to be true.

Rivers Solomon’s Model Home is a haunted house story which deals with the very real horrors of white supremacy and abuse. The writing is fantastic. This novel is deeply unsettling but within all the horror (and there is a lot), there are also small moments of light. I loved the very complex, imperfect family relationships: both between the siblings and between Ezri and their child. These relationships and how they shift and develop is so important to the novel.

I also think this novel does very interesting things in the way it narrates disability (such as mental illnesses, trauma related reactions, neurodivergence, diabetes…) as always present in the way that these characters with all their experiences are present.

While I read this book in one day because I really needed to know what happens next, I listend to Joy Oladokun’s latest album. In their song “I’d miss the birds” they have a beautiful line (about Nashville) which resonated also so much with Model Home:

“made it farther than they thought I would

But it doesn’t mean I should hang ’round and suffer

This world on fire still has good to discover”

UPDATED: Anne Ursu: Not Quite a Ghost (2024)

A wonderful middle grade novel. Violet moves with her family into a new (but very old) house and finds that there is something in the attic – the attic which also happens to be her room. And while she deals with this troubleing haunting, Violet also has to navigate old and new friendship dynamics. And if that weren’t enough Violet starts to show a multitude of disableing symptoms. This novel is a wonderful story about friendship, it is a creepy ghost story, but above all also a story about ME/CFS and how the medical system often fails us.

Jasmine Walls, Teo Duvall (Illustrator), Bex Glendining (Colorist), Ariana Maher (Letterer): Brooms (2023)