#ReclaimHerName – or maybe don’t?

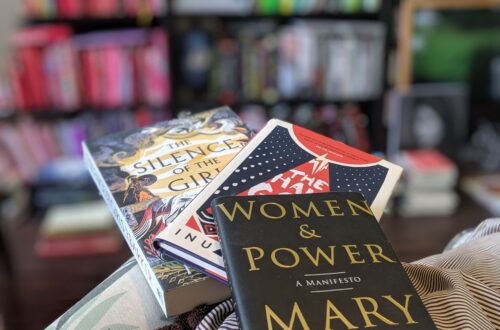

In 1939, Ann Petry published her first short story “Marie of the Cabin Club” though the name “Ann Petry” was not listed as the author, instead, it was “Arnold Petry”. Like her, throughout history, women have taken on masculine pen names in order to publish their writing in a sexist and misogynistic (publishing) world. To celebrate its 25th birthday the Women’s Prize for Fiction has put together a box of books by authors who had been published previously under masculine pen names. In these new editions, their (supposedly) ‘real’ names are used. The cover designs – all by female designers – look striking and many people have been fanning over this box, though it will not be available to purchase in print. The physical box will be donated to some selected libraries in the UK and for everyone else, the books will be available to download for free.

But while the reactions to this initiative have been very positive – not to say pretty enthusiastic – so far, my first bodily reaction was to flinch. Of course, there are clear-cut cases in which writers have used male pseudonyms to have better chances to get published (and/or acknowledged) and who would have loved to be published under their given names. Ann Petry did just that and went on to publish under her name. The use of male pseudonyms often points to the inherent power dynamics in publishing and in general in the realm of creating art. But that is not all. I feel this compilation with its very unifying approach glosses over many complexities and not always does a favour to the writers in question. And as the writers are all (at least, as far as I could see?) dead, they could not weigh in.

Two years ago, when Akwaeke Emezi was longlisted with their fantastic debut novel Freshwater, the Women’s Prize for Fiction had a great chance to re-evaluate their prize and to ask important questions: Who do they want to support and feature? How can the prize be more inclusive? But instead of thinking up ways how the prize might become a prize for people of all marginalized genders, the wordings by the judges and the prize meant that Emezi was constantly misgendered in the coverage. (The prize did announce that they would “formulate a policy around gender fluid/transgender/ transgender non-binary writers to provide clarity for the Prize in the future” (The Bookseller) but on their website, the first FAQ entry is still “Why is the Women’s Prize for Fiction only open to women?”.) So, that this year’s campaign #ReclaimTheirName is not particular inclusive does not come as a surprise.

In an article at the Guardian, novelist Kate Mosse, the founder of the Women’s Prize, is quoted in saying that the promotion intends to ensure “that on the shelf, women are visible”. To do so with a focus on names solely seems under-complex, as the way names are gendered is dependent on cultural context, languages, and ultimately also time. But what troubled me, even more, is the wording: “[W]e have put their real names [my emphasis] on the front of their work,” states the Baileys website. (Baileys is a partner in the project.) What are ‘real names’? What they mean, apparently, are the name the writers were given/ which appeared in official documents. In many cases, these names did conform to the names the writers have mostly identified with – but again not all. To call these names ‘real names’ is a very narrow perception of names and the validity of self-chosen or changing names (and potentially damaging, especially for trans and queer people). And as the author Lizzie Huxley-Jones wrote on Twitter:

My critique of the #ReclaimHerName (who exactly is doing the ‘reclaiming’ by the way?), lies exactly there: to put all these different writers with different histories into one single box – figuratively and not so figuratively – pushes them into very narrow gender boxes. Some people might have enjoyed putting on a persona or saw their pen name as a part of their creative process. For others, the name could have meant more. While I think it is very difficult to map current identities and labels onto historical lives, I believe in the careful and nuanced descriptions and evaluations of these lives which lay bare queer practices and desires disrupting the heteronormative gaze. If we open our perception for these things, we might see how ‘pseudonyms’ sometimes were much more than just that. As Sally Newman wrote already 15 years ago in her article “The Archival Traces of Desire: Vernon Lee’s Failed Sexuality and the Interpretation of Letters in Lesbian History” about Vernon Lee (who is included in the Women’s prize’s collection):

It seems clear to me that Vernon Lee was much more than a pseudonym; it was, as Lee’s executor, Irene Cooper Willis, makes clear in the following letter, her chosen name and identification (whatever that may have encompassed): “I must ask you to call [the catalog] the Vernon Lee issue. Except to mere acquaintances she was never known as Miss Paget: and she would have objected strongly to being referred to as Violet Paget in connection with her writings and papers. She was always known and thought of by her friends and readers as Vernon Lee” (Irene Cooper Willis to Professor Carl Weber, Colby College, 22 August 1952, Miller Library, Vernon Lee collection, Colby College, Waterville, Maine).

Sally Newman. 2005. “The Archival Traces of Desire: Vernon Lee’s Failed Sexuality and the Interpretation of Letters in Lesbian History.” In: Journal of the History of Sexuality

Vol. 14, No. 1/2, Special Issue: Studying the History of Sexuality: Theory, Methods, Praxis, pp. 51-75.

We might also see how at times female pronouns were combined with masculine names and at other times writers used male pronouns for themselves. We might see how these things were fluid. And of course, there is the special case of Michael Field in which not one but two people made up the persona. Another queer (and partially troubling) history which seems to be more obscured through the dissolution of the pen name than highlighted.

The cover designs put the names in the focus. They are written in a considerably larger font than the titles of the works (which on the announcement photos are often not even readable). This focus on the (presumably) FEMALE name might be empowering for some – and fully in line with the hopes and wishes of some of the featured authors! – but feels like an un-queering of literary history with regards to others.

Further reading (will add when I find more; also thanks to @bankrupt_bookworm who pointed me to some of these):

- Grace Lavery’s twitter thread on why George Eliot is referred to with the ‘pen name’ and female pronouns

- Grace Lavery: “Down With These So-Called “Gender Categories”!“

- Lucy Powrie’s twitter thread on the author notes in the #ReclaimHerName books

- Sam Hirst’s twitter thread on lacking nuance and erasing history

- Lizzie Huxley-Jones’ twitter thread on writers’ autonomy and some choices with regards to race

- Sian Cain “‘Sloppy’: Baileys under fire over Reclaim Her Name books for Women’s prize” (The Guardian)

- Olivia Rutigliano “The #ReclaimHerName initiative ignores the authorial choices of the writers it represents.” (Lithub)