The Great White Feminist Novel

On November 28th, Margaret Atwood wrote a tweet which excited many. Thirty years after the publications of her seminal dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale (and during its successful run as a TV series), Atwood announced that she was writing a sequel: The Testaments will be published in September this year.

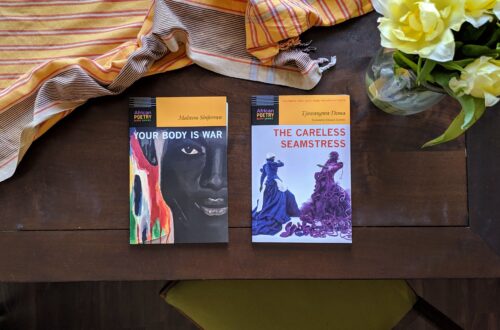

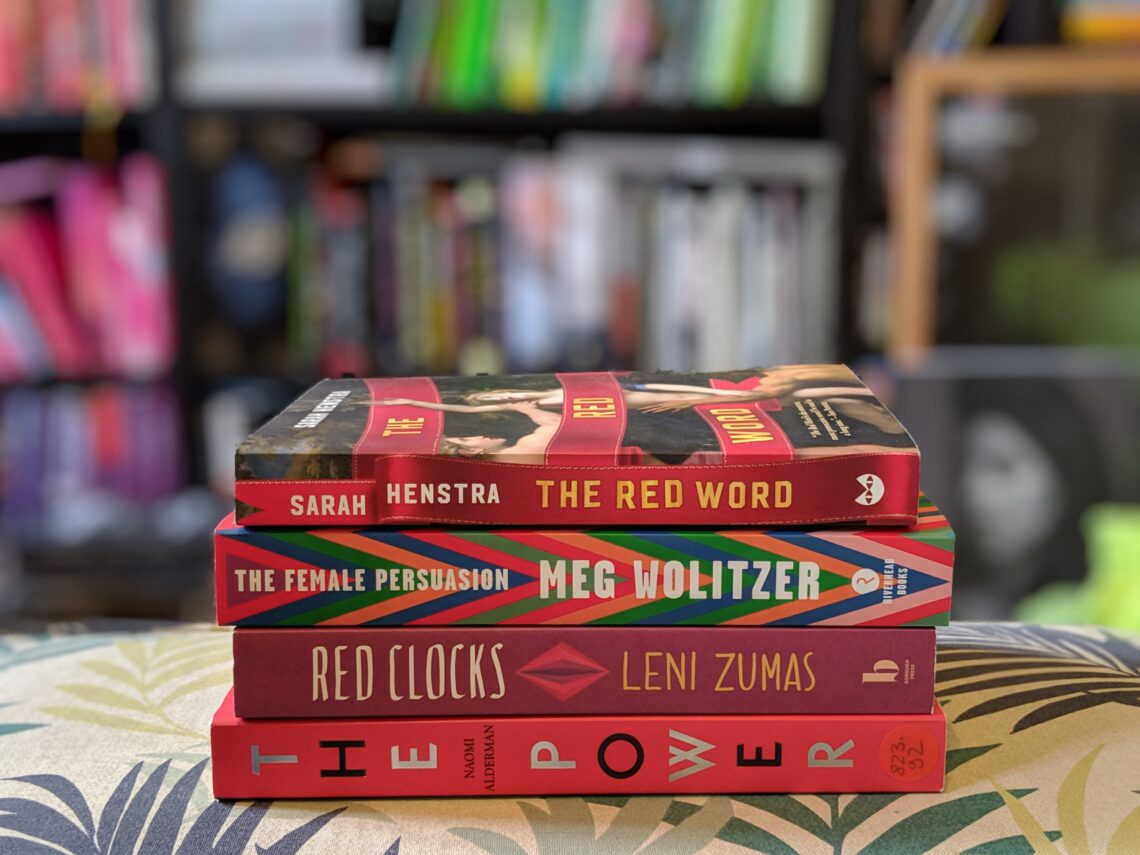

It seems to be a good time for grand feminist novels which do not hide their feminist themes but make them front and centre. In 2017, Naomi Alderman won the Women’s Prize for Fiction with her dystopian novel The Power in which teenage girls gain physical power and power relations start to shift. Last year, Meg Wolitzer published The Female Persuasion, a 450-pages long examination of different feminist generations and the (im)possibilities of activism and feminist publishing. Alone in 2018 there were novels published such as Sarah Henstra’s The Red Word about rape culture at a US campus, Sophie Macintosh’s The Water Cure about patriarchal violence and female enablers, Leni Zuma’s Red Clocks about reproductive health in a dystopian (?) society which has outlawed abortion and grants rights of life, liberty, and property to every embryo, Angela Chadwick’s XX about ovum-to-ovum fertilisation, and Christina Dalcher’s Vox in which women are not allowed to say more than 100 words per day.

I picked up a lot of these novels because the promise of the great, relevant feminist novel lures me in again and again. But in the end, I usually am left wanting and feeling mostly dissatisfied. A lot of my dissatisfaction stems from the discourse around these novels which put them on a pedestal and make them more than just particular perceptions but rather allow them sweeping statements about women ™.

In her critique of the TV adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale, Nayuka Gorrie writes:

This whitewashing in the show and its subsequent whitewashed analysis wouldn’t sting as much if the show didn’t rely so heavily on narratives taken from the lives of black people. For black people these stories do not have to be imagined as a dystopian future. The handmaids are slaves and many nations including Australia have a black slave history. We don’t have to look further than our own families. In this country black children were stolen from their black mothers, black women were forced to have hysterectomies or given them without their knowledge.

A lot of dystopian feminist writing by white, straight authors, in particular, could be summed up with “What would happen if we were treated as many marginalized women/ non-binary people are treated right now or at least have been in the past?”. There are other elements which find their ways into numerous of these novels: they indulge in violence against women or make it even look entracing (The Water Cure, for examples, could be criticised for aestheticizing pain and violence against women and the way (white) women’s vulnerability is portrayed), they focus on white women’s narratives, the moment it is about reproductive rights the books rarely acknowledge a non-cisnormative perspective, only a limited amount of topics is understood as feminist, heterosexuality remains a set norm and queer characters – if present at all – often function as the backdrop to straight women’s development. A singular book still might be a great read but it becomes a problem if it is a trend throughout the genre and if it is something which is rarely remarked upon in the more visible reception. And there seems to be a trend to laud novels as the new great feminist novel which fit more or less comfortably within the parameters of “white feminism” – whereas the term does refer to specific politics not so much to the identity of the writer or protagonist though, unsurprisingly, there is a huge overlap.

The Female Persuasion by Meg Wolitzer was published last year and accrued positive reviews in outlets such as the LA Times and the NY Times (the latter penned by no other than “white feminism” poster child Lena Dunham). This very readable novel follows Greer Kadetsky. In her first year at university, angry with her parents, and organizing against a guy, who harasses young women on campus, she meets Faith Frank at a lecture. Faith is a seasoned feminist in her 60s who runs a small magazine. Greer is absolutely fascinated by Faith’s talk and this is not the last time their paths will cross. Faith’s magazine will lose its funding but she will be enabled to start a huge feminist foundation organizing summits. Greer will start working for her. But is it a feminist wish come true?

Wolitzer touches upon gender roles, grief, sexual harassment, finding one’s vocation, friendship, different generations of feminism, activism and funding, love. But barely any of these themes are developed fully. It becomes particularly apparent when we look at one of the central themes: the differences between younger and older feminists. These differences are often mentioned in throw-away comments. It feels like the novel is written by someone who knows these debates only through third-hand (!) stories (“There are now younger feminists who have web pages and want to be more inclusive.”). Greer and Faith are constructed as oppositional but at the same time they are very similar – the latter could have been used to make a more complex argument about political differences but is not. There is no nuance which could point towards the fact that differences are not just generational but interlinked with identity categories such as race, ability, sexuality, class and/or political schools. At its core, it is a novel on struggles within white feminism. Characters which offer other takes are sidelined throughout the narrative. For examples, there is Greer’s close university friend, Zee, who is a lesbian activist and is the one who introduces Greer to Faith’s work and takes her to the lecture. Besides being told that these two are best friends, it never made a lot of sense to me why they are actually friends (what does Zee get out of this friendship?). Everything we are told about Zee and her development sounds interesting and I would have liked to read more about her, but that is not what we get because Zee is only employed as a foil for the straight character (Greer) to enable her growth. (But at least, the portrayal is better than in The Red Word where the queer/lesbian activists are shown as almost just as bad as the raping frat boys – the main protagonist of the novel is, of course, a straight woman.) The Female Persuasion could have been a great novel dissecting the pitfalls of “white feminism” but it is more invested in the protagonist’s hetero relationship than the intricacies of feminist thought and action.

Naomi Alderman’s The Power offers a way more diverse cast of characters and tells a story of global scope. Seemingly overnight (mostly) teenage girls all over the world gain immense physical power: they can cause agonising pain and even death with just the touch of their hands. The novel follows a hand full of characters on their endeavours in a fast-changing world. With the girl’s (and women’s) gain of this new physical power, there is a shift in power relations which often puts men into precarious positions. Through the depiction of these changes, the novel tries to put a mirror to our patriarchal, sexist world, but, for me, it was a novel of missed chances. The Power asks exciting questions, the answers it offers though left me wanting for more. For one, the global approach, unfortunately, falls back on stereotypes at times instead of nuanced discussion what a power shift within different political, religious, cultural systems might look like. But furthermore, I struggled with the entire direction of the novel. Following its logic, patriarchy solely exists because men as such are physically stronger – so the moment women gain physically the upper hand in Alderman’s tale the power relations switch around and women start to oppress men. While I can see the point of power corrupting everyone regardless of gender, the fact remains that systems of oppression are not just a question of innate (“biological”) physical superiority. The novel foregoes a worthwhile exploration of how patriarchy might be dismantled when marginalized people gain power and bring with them not only their own experiences of being oppressed and the ongoing trauma but also their decades of work against this kind of oppression. Instead, and in spite of its multiple perspectives, it goes for a rather simplistic model.

The Power and The Female Persuasion are two of the most prominent examples which both start out with very interesting premises but, to my mind, still fall short in their execution. Even though, I did not hate either. Both novels did entertain me. There were passages I enjoyed, some characters I was interested in. But I could not relate my reading experience to the way the books were praised. The political climate we witness in many countries and in global politics, easily explains the intense want and need for feminist narratives. But some of the books which are celebrated as such remind me of other forms of the commodification of feminism like punchy t-shirt slogans by huge retailers. This is not to say that there haven’t been great novels by feminist writers or great novels dissecting feminist themes or great novels lending themselves to feminist analysis (all these things not necessarily have to be true for one book, they are not requisite for each other) in the last years. However, it is interesting to note which books are discussed as “the great feminist novel” and which books rarely get the label.